We’re talking about the end of time, judgment, hell, and associated fires. Last week, we looked at the outer darkness, a place absent of light, a place absent the presence of God who is the source of all light and who dispels the darkness.

The opposite of outer darkness is the presence of God. The final judgment will result in those who find themselves in the presence of God and those who find themselves in outer darkness, out of God’s presence, out of the light.

In the parable of the 10 virgins, those who went into the banquet hall when the bridegroom came found themselves in the presence of God. In the parable of the servants, it’s the five- and the two-talent servants. And in the parable of the sheep and the goats, it’s the sheep. These are the ones who find themselves, in the judgment, in God’s presence.

John talks about how to enter into the presence of God though a door which I’m going to call the door of grace. Today we will discuss several doors of grace: The door to the sheepfold, the door of the narrow way (the narrow gate in Matthew) and the door described with Jesus knocking on it in Revelation. These doors teach us something about God’s grace and how to enter into God’s presence—how to avoid the outer darkness.

Scripture has many references to doors. The only legitimate way into the sheep pen, says John, is through the door. All other ways are illegitimate:

“Truly, truly I say to you, the one who does not enter by the door into the fold of the sheep, but climbs up some other way, he is a thief and a robber. But the one who enters by the door is a shepherd of the sheep. To him the doorkeeper opens, and the sheep listen to his voice, and he calls his own sheep by name and leads them out. When he puts all his own sheep outside, he goes ahead of them, and the sheep follow him because they know his voice. However, a stranger they simply will not follow, but will flee from him, because they do not know the voice of strangers.” Jesus told them this figure of speech, but they did not understand what the things which He was saying to them meant.

So Jesus said to them again, “Truly, truly I say to you, I am the door of the sheep. All those who came before Me are thieves and robbers, but the sheep did not listen to them. I am the door; if anyone enters through Me, he will be saved, and will go in and out and find pasture. The thief comes only to steal and kill and destroy; I came so that they would have life, and have it abundantly.

“I am the good shepherd; the good shepherd lays down His life for the sheep. He who is a hired hand, and not a shepherd, who is not the owner of the sheep, sees the wolf coming, and leaves the sheep and flees; and the wolf snatches them and scatters the flock. He flees because he is a hired hand and does not care about the sheep. I am the good shepherd, and I know My own, and My own know Me, just as the Father knows Me and I know the Father; and I lay down My life for the sheep. And I have other sheep that are not of this fold; I must bring them also, and they will listen to My voice; and they will become one flock, with one shepherd. (John 10:1-16)

Why is the door to the sheepfold a two-way door? Note that to enter, Jesus says, is to be saved. But once saved, there apparently is ingress and egress. In and out. It seems that being saved by grace enables us to be active both inside and outside the fold. It implies that there is work to do outside the fold. Inside, the fold is a place of safety, a place of community, a place of equipping for work. Being inside the fold enables us to be effective outside the fold, it seems.

The way of grace is not a jail. It is not a place of confinement. It is a place where you are prepared to go out. The saved “come and go”. The work that a sheep must do is to find a pasture. The work that those with grace must do is to show grace This is a door of grace, the door to the sheepfold.

But another door of grace, a way into the light, away from the outer darkness and a way into the presence of God, is the narrow way spoken of in Matthew as a gate:

“Enter through the narrow gate; for the gate is wide and the way is broad that leads to destruction, and there are many who enter through it. For the gate is narrow and the way is constricted that leads to life, and there are few who find it.” (Matthew 7:13-14)

This is perplexing, particularly given the following:

After these things I looked, and behold, a great multitude which no one could count, from every nation and all the tribes, peoples, and languages, standing before the throne and before the Lamb, clothed in white robes, and palm branches were in their hands;… (Revelation 7:9).

Here is a multitude no one could number—infinity, unlimited. It is a metaphor for something where there’s always room for one more. The first passage says few can get through the narrow gate, while this passage says everyone gets through the narrow gate, including those who are not Christians or Jews—people from “every nation, and all the tribes, peoples, and languages”. How can the gate in Matthew be exclusionary if such a great multitude is able to get in?

Who then is excluded? The door in John is narrow, but it is a legitimate way to the kingdom. The narrowness is often applied to the way that we’re to live our lives—through narrow self-denial known, Jesus said, as the way of the cross:

Then Jesus said to His disciples, “If anyone wants to come after Me, he must deny himself, take up his cross, and follow Me. For whoever wants to save his life will lose it; but whoever loses his life for My sake will find it. For what good will it do a person if he gains the whole world, but forfeits his soul? Or what will a person give in exchange for his soul?” (Matthew 16:24-26)

The phrase “come after Me” in the passage above is a reminder of the sheep in John, who follow their shepherd. For millennia, since the beginning of the church, church fathers have called on their flocks to practice self-denial and self-deprivation as a way to salvation. It is on the basis of this narrowness of the way of the cross. People like Simon Stylites, who sat atop a column in the (now Syrian) town of Aleppo for 37 years, are the ultimate expression of this mindset. Vows of silence and chastity, the wearing of itchy hair shirts and the practice of castration all stem from the view that the way is narrow and demands such acts of self-denial and self-deprivation.

And yet, in the context of other passages (including the one we just read), narrowness, self-denial, and self-deprivation amount to the opposite of what has been long assumed and preached and practiced. Jesus says:

“Do not judge, so that you will not be judged. For in the way you judge, you will be judged; and by your standard of measure, it will be measured to you.” (Matthew 7:1-2)

The narrow way is the way of grace. The notion that one can make oneself holy through self-denial and effort is just plain wrong. Only God’s grace can make us holy. The call to suspend judgment is a call to community, a call to extend to others the grace we have been given.

The way of grace narrow in the sense that it is not easy and not intuitive. It is so easy to fall into the trap described in this passage:

“Not everyone who says to Me, ‘Lord, Lord,’ will enter the kingdom of heaven, but the one who does the will of My Father who is in heaven will enter. Many will say to Me on that day, ‘Lord, Lord, did we not prophesy in Your name, and in Your name cast out demons, and in Your name perform many miracles?’ And then I will declare to them, ‘I never knew you; leave Me, you who practice lawlessness.’ (Matthew 7:21-23)

Participating in the business of God and doing things for God seems intuitive and compelling. But the judgment reserved for people who fall into this trap is: “I never knew you.” This is not the narrow way. What ought to be denied is the self-effort toward righteousness. The narrow way, I believe, is narrow not because it is exclusionary but because it is personal, it is individual, it is one by one. The way of grace is traversed. Grace is dispensed by personal need, like the garments at the wedding feast—each gets just what they need, just the right size and just the right shape. Grace is narrow because it is personal, it is individual, it is unique. Your grace is just for you. My grace is just for me.

Although there are many other doors that we might look at as the doors of grace, I want to look at one more: Jesus says to the churches:

‘I know your deeds. Behold, I have put before you an open door which no one can shut, because you have a little power, and have followed My word, and have not denied My name. (Revelation 3:8)

Doors can be opened and doors can be shut. It seems that for Jesus the door is always open. The open door is the way of grace, and fortunately, Jesus has an open-door policy:

Moreover, they shall take some of the blood and put it on the two doorposts and on the lintel of the houses in which they eat it. (Exodus 12:7)

The blood is why the door can be opened, it is the price of salvation, it is the way of the cross. By standing at the door Jesus protects us and assures our salvation. The assurance is confirmed by the blood on the doorposts. However, it seems that the tendency of mankind is to shut the door. Fear and insecurity makes us retreat into isolation, and we shut the door.

When the door is open, the good shepherd stands beside it, providing safety and refuge and comfort. When we shut the door, we introduce an element of uncertainty about what is on the other side of the closed door. The open door is the portal for all who hear the voice of God to respond to him.

One of the most remarkable features about the door-and-the-shepherd metaphor is the notion that there are other sheep not of this fold, who also hear and respond to the voice of God. Because as we see in Revelation, the multitude comes from every nation, tribe, and tongue.

The last door in the Bible is found in the last letter to the seven churches. The picture is described toward the end of this passage:

I know your deeds, that you are neither cold nor hot; I wish that you were cold or hot. So because you are lukewarm, and neither hot nor cold, I will vomit you out of My mouth. Because you say, “I am rich, and have become wealthy, and have no need of anything,” and you do not know that you are wretched, miserable, poor, blind, and naked, I advise you to buy from Me gold refined by fire so that you may become rich, and white garments so that you may clothe yourself and the shame of your nakedness will not be revealed; and eye salve to apply to your eyes so that you may see. Those whom I love, I rebuke and discipline; therefore be zealous and repent. Behold, I stand at the door and knock; if anyone hears My voice and opens the door, I will come in to him and will dine with him, and he with Me. The one who overcomes, I will grant to him to sit with Me on My throne, as I also overcame and sat with My Father on His throne. The one who has an ear, let him hear what the Spirit says to the churches.’” (Revelation 3:14-21)

Despite the assurance that Jesus has an open door that can’t be shut, this passage says that churches (here, specifically, the Laodicean church) have shut the door and explains why: The feeling that I am rich and in need of nothing shuts the door of grace; to retreat behind my goodness, to isolate myself in my own piety and my own good works is to shut the door of grace; to fail to see that I am wretched, miserable, poor, blind, and naked is to shut the door of grace.

Here we see, at the end of the Scriptures, in the Book of Revelation, the same story that we see in the garden, when God calls into question Adam and Eve’s spiritual self assessment. As they are hiding from God after the eating of the fruit, he asks them why they are hiding. They answer: “Because we are naked”…

And He said, “Who told you that you were naked? (Genesis 3:11)

Adam and Eve have no viable self-assessment. Their self-assessment of their spiritual condition is called into question. With the Laodiceans, it is the opposite: They think they are well clothed, but Jesus says they are not just naked, but wretched, miserable, poor, and blind as well. Still, just as in the garden, we see the offer of grace. The picture is one of God knocking at the closed door.

Many famous paintings of this well-known passage from Revelation had been made. But in 1853 William Holman Hunt drew a picture with a door that has no external handle. It can only be opened from the inside, only opened by the one who closed it:

Grace is not pushy, it seems. There is nothing intrusive about grace. Grace is always at the door but we must always open the door in order to receive it. More precisely, because of God’s open door policy, we must not shut the door of grace.

What does it mean, to “open the door of grace”? Or more precisely, what does it mean to not shut the door of grace? Why does grace not traffic in the lukewarm? Why does Jesus say “I wish you were either hot or cold”? Why are extremes preferred to the lukewarm? How do these pictures of the door of the sheepfold, the narrow door, the closed door with Jesus knocking, help you understand more about God’s grace? What role do you have in these metaphors? How much self-denial is actually called for? How narrow is the door? And how does one not shut (keep open) the door of grace? How inclusionary is the door?—Do you have to actually believe in the door to use it? What about sheep who are not of this fold?

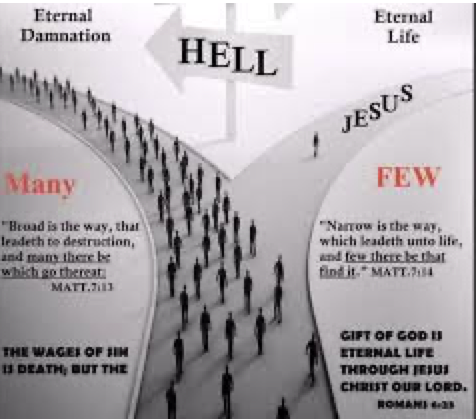

Donald: I found this picture interesting:

The pathways are equally broad. The picture make it looks pretty personal. Many are going to hell. This is the picture in our minds. It’s not exactly the one we had when we were Adventists kids but it’s not that dissimilar. Another interesting picture show Jesus at a door with the handle on the inside, presumably, where we stand.

Michael: Christian teaching perpetuates such images. They are worth questioning, especially given their effect on people, causing them to take the route of self-denial, to assume that the road is a very, very hard one to take and requires much effort, like the lone figure in Donald’s image going the way of Jesus. Such images perpetuate and exaggerate an opposite understanding of grace—a grace that is hard and can only be reached through one’s own effort.

David: Christians have had this picture at least since the Crusades, except theirs shows all Christians taking the right fork and all infidels going off to the left. That is still the picture most Christians cling to. That’s what they think it means to follow Jesus, and if you don’t follow Jesus, you’re not a Christian and you’re going down the wrong path.

Don: That’s why to me, the metaphor of the door is so compelling. You don’t have to believe in the door, you don’t have to know how the door is constructed. In order to use the door you simply walk through it. It’s an empty space. It’s a portal. It’s not a barrier to be analyzed. You don’t even have to believe in it.

David: That is the Way—the Dao—of the Daoist. The way, the road, and the door amount to the same thing.

Donald: A traffic jam on a highway that occurs because the road narrows doesn’t mean you won’t get through it. It’s personal. If everybody got through at one time, it would not be personal. But certainly the image depicts one choosing Christ while the masses choose the other pathway. It’s not like all those people were trying to go down the right road. They chose the wrong road. There is a wrong road.

Chris: I can definitely remember that picture, from my Sabbath school days But what if we have that picture wrong? What if the door is always open and we’re the ones that close it? The picture always shows us needing to open the door. But is the door truly closed or is the door open and in the end we’re the one that closes it?

Donald: Very interesting point. Quite a different way of seeing it. Why is there a barrier between us and Christ? A solid barrier—there’s no window in that door.

Chris: Isn’t it like grace—always available? And isn’t it we who choose not to accept it? The door of grace is open to me. Always. Maybe the picture doesn’t well depict the action behind the door and what’s occurring with the door. Does it start closed? Or was it closed?

Don: Jesus says he sets before us an open door that no man can shut.

David: The door that can’t be shut is the Dao—the Way—that you are on, unless you choose to get off it. You are always on the Way unless you choose to get off it. So in that sense, the door is always open if you choose to go through it—and most people do, without knowing anything about the Way or the door. They simply follow the trajectory in front of them, the path that their life takes, and that’s good enough for what Christians think of as salvation or what Daoists think of as enlightenment and eternal life at the end of the road.

It’s a passive thing. It’s not an active thing. But these stories suggest that you need to be active. “Zealous” was a word in the quotation from Revelation. It is a word demanding activity, and a word that has been responsible for much suffering and death around the world. .

Sharon: What about “Behold, I stand at the door and knock”?

Chris: There’s some beauty in that passage. Because if my door is closed in the first place, he doesn’t just walk on by. He continues to try. Looking at this from the standpoint of grace, he continues to try and extend that grace to me.

Maybe even though I close myself off, or reject grace, that isn’t the end of it for God. He’s still going to pursue me, to come by, to continue to try and extend his love and his grace towards me. The question is am I then going to accept it, after I have initially closed myself off to it?

Sharon: Are we walking in to the grace of Jesus? Or are we walking out to the grace of Jesus?

Don: According to the sheep metaphor, there’s a walking-in and a walking-out. Once you’ve walked in, it says, you become saved. And once you’re saved, you can go in and out. John: “I am the door. If anyone enters through me, he will be saved and will go in and out and find pasture.”

Sharon: And so we have osmosis. Going through, all ways. So grace is an open system, and it mobilizes us to then share that with others.

Don: Yes. But going back to Donald’s illustration of the highway with many people taking the left fork and one going down the so-called narrow way on the right, you cannot hide the fact that the narrow way, which is the way to salvation, is the way of grace. That has to be a given, it seems to me, and if so, the great multitude in Revelation—an infinite number, immeasurable, with always room for one more—is a pretty inclusive picture of the end product of the narrow way: A picture of grace and acceptance. I can’t accept that the narrow way is the way of self-denial, which is what we always picture it as.

Michael: People think that if you’re saved, then you’re happy. Or if you get grace, then your life is different. There is cause and effect. It depends on how you see it. If you see life as unfair—you’re a good person but everything happening around you is bad, that’s one way. But you can also look at the other way: Life is not fair—you’re not a good person, but everything around you is great!

What I’m trying to say is sometimes it’s hard to see grace. That’s why such teachings gain a hold: If I self-deny, in heaven I will be happy. But I can live a really bad life if I stop denying myself!

Donald: Why is it so common (at least in my experience) for us to communicate about works rather than grace? We don’t want to talk about grace. Is it because we’re confused about it and it just doesn’t make sense to us? It’s not that I earned this. It’s much easier to talk about “narrow is the way” and you are earning it and most people won’t go to that effort. So what hope do I have? That’s certainly not the way we want faith to be understood.

Reinhard: To me the figure of speech of the broad and narrow way is just to describe it for humans to understand. It is easy to do because in life I think the tendency of most people is to shy away from God’s command. Psalm 23 says if we are true believers God will lead us through the path of righteousness. Psalm 105 talks about God lighting my steps. I think if we walk in the right way according to God’s command we don’t have to worry about not being accepted. God will be the judge, but believers know what is prescribed, they know what we need to do.

David: I have to challenge the notion that we we tend to go against God’s will. I think that on the contrary, we tend to the good. Don has mentioned several times in class, and I think we’ve all agreed, that if you look around there is more good in the world than bad. And there has to be, because if there was more evil than good in the world, we would end up in total chaos, the devil would win, and the creation would be destroyed.

It isn’t because we tend towards good, it’s that we tend to be on the right path to begin with. That’s what I get out of what Jesus is saying, that you really don’t have to work too hard at this, you’re already on the right path. Just just keep doing it. You’re following me whether you know it or not. That is the message that I get.

Don: It’s certainly counterintuitive. It’s certainly not the prevailing view of Christianity that we’re all on the right path. I think Donald’s picture of everyone going to hell is the prevailing view. But I agree with you.

Michael: When Jesus says that everybody who came before him are robbers and thieves, who was he talking about? Who are the people who came before Jesus who were robbers and thieves?

Don: Good question.

Donald: What does Mrs. White say about all this? Would that change our perspective at all? And should that play into this conversation? What insight did she have? Maybe we can say that’s not really how we perceive it, but to not include it as part of this discussion seems a bit odd.

Sharon: It’s amazing to me how much Steps to Christ supports this whole notion of grace and an unconditional acceptance of the love of Jesus. In the last two weeks I’ve been through the book twice, and Ellen White is very clear that Satan has marred the character of God in order that we would be fearful and not be eager to come to him. But if you want a biblical Spirit of Prophecy grounding for this discussion, just go back and read Steps to Christ again. .

Chris: I just quickly googled “Ellen G. White and grace” to see what might pop up, and in one of her writings, she says we should never have learned the meaning of this word “grace.”

Donald: What does that mean?

Chris: Because we have fallen, we are now forced to try to understand and learn what grace is.

Donald: So it’s a difficult concept.

Chris: We’re trying to make human constructs of something we weren’t ever supposed to know or worry about, and now here we are trying to grapple with it, define it, work through it, when it’s just what has always been. The law has always been and grace has always been. Were we supposed to understand or know this?—Not according to Ellen G. White.

David: She is just lamenting the fact that we fell. If we had never fallen we’d have no need of grace. If you’re always in God’s presence, what more grace do you need? I think that’s all she meant, not that there is some badness inherent in knowing what grace is. It just means that if you have to worry about grace, you’ve fallen.

Chris: You’re an undeserving human being according to her because she says grace is an attribute of God shown to undeserving human beings.

David: I too, did some googling and as far as I can tell, it seems that the robbers and thieves (to answer Michael’s question) were the usual suspects: The Pharisees and Sadducees.

Don: Exactly.

Donald: What would a biblical scholar make of this conversation?

Michael: I have discussed many of these topics with seminarians, without much enlightenment.

Carolyn: My idea of grace is simply like a door that we walk through. And once we do, we have the love of Christ. We have the Holy Spirit to guide us. It is a daily walk with God but without fear, because we know that we’re on that right path.

Reinhard: A Bible scholar has said that despite Jesus giving us the task to evangelize, since AD 37 until the present day, only about 33% of people have heard the gospel. I would guess it’s more than 50% now. Whether or not people will be saved by grace or works, the litmus test is whether they follow God’s Word, God’s command. I think that’s the only thing that will earn God’s grace. How will doing wicked things earn salvation? Will God still give free grace to those who don’t know his commandments?

The last six of the 10 commandments concern human relationships. We must not do things to hurt our fellow men. That is a kind of passive instruction. But Jesus said we must love our fellow man, which to me gives us freedom to act. If we follow God’s law with love, we not only do not do what is prohibited in the 10 commandments, but we are actively going to help other people—to feed the poor, to clothe the naked, and so on.

We will be measured against God’s law when we receive the grace of God. People without faith will not see God. People who follow God and do his commandments and do what Jesus said will be saved. The people who never heard the gospel or heard about Jesus may be saved. We don’t know how God will judge them.

David: What if the victim in the parable of the Good Samaritan was a violently abusive man who just robbed a bank with a couple of fellow reprobates, then cheated them and ran off with their share of the loot, so they chased after him, caught him, beat the living daylights out of him, and took all the money? He was worse than the other two robbers because he not only robbed the bank but he robbed his friends as well!

If he had known all this, would the Good Samaritan have stopped to help him? Surely, the Good Samaritan—Jesus, God—would not care what the man had done. They would save him anyway.

Michael: The Bible that says that God rains on the good and the bad. He does not discriminate.

Donald: What Jesus says about a rich man getting to heaven sounds pretty narrow too.

This is confusing business. Maybe Chris has got it right that grace is something that human beings were never meant to understand.

* * *

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.