As a professional educator, Jason led today’s discussion of education as a driver and component of culture, religion, technology, and our view of God. And one of the things that I think affects, in a major way, our view of God is education. Since we have professional educators in the class, I thought it would be well to listen to some of their perspective on education and see how that affects our view of God. —Don

Jay: How might education shape how we view God and how we view the attributes of God? Last week, Michael mentioned how our psychology may introduce conflict and cause cognitive dissonance with how we view God, or how we should view God. Certain specific psychologies are used to educate kids—to move students through the learning process.

Two fundamental pillars of educational psychology help to shape the learning structures—the pedagogy—that teachers, schools, and formal educational systems put in place to educate our students. The first is behavioral psychology, whose influence led to a shift from classic conditioning to operant conditioning. Classic conditioning is what Pavlov’s dog went through: You ring the bell, the dog salivates—a very specific response based on a very specific stimulus.

Education started that way. But educational psychologist BF Skinner led the change to operant conditioning—positive and negative reinforcements that help students learn. Students receive positive rewards for doing the right thing and negative consequences for doing the wrong thing. Behaviors that are rewarded tend to happen with greater frequency than behaviors that result in a negative consequence.

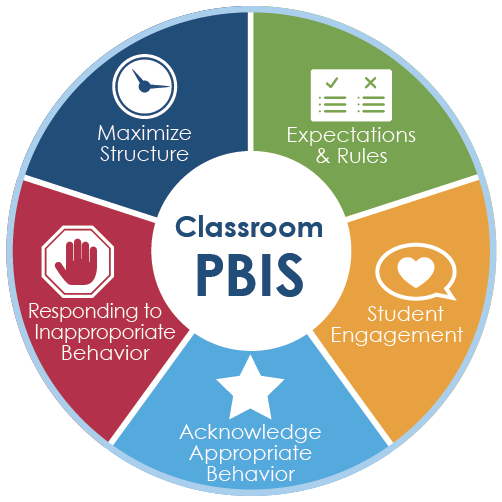

Today we have a system that’s called PBIS—Positive Behavioral Intervention and Supports, which is based upon operant conditioning. The figure below is an example out of Florida of what a PBIS classroom looks like.

It shows specific acknowledgement of appropriate behavior. While there are some very specific responses to negative kinds of behavior, teachers tend to give rewards for positive things. This isn’t very far removed from how parents teach their children. Even our grading system is set up this way: The A’s and B’s are rewarding grades While D’s and F’s are “consequence” grades. Thus, our educational system is based on positive and negative reinforcement.

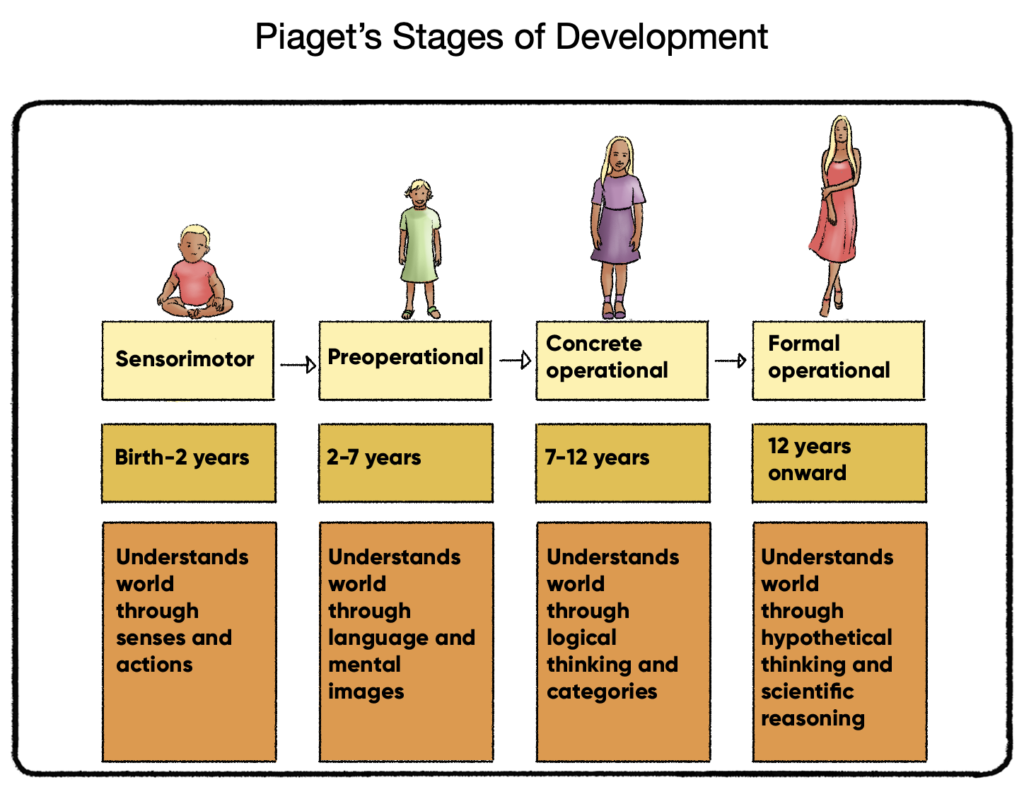

The second major influence in education is developmental psychology; in particular, the work of Jean Piaget and his stages of psychological development that start with a sensorimotor stage that occurs between ages zero through two years old; then a “preoperational” stage, which is through ages two through seven; then a concrete operational stage (ages seven through 11) and finally, after 11–12 years old, the formal operational stage.

In the sensory motor stage, infants and toddlers use their senses to develop and learn within the world. A sign of the end of the sensorimotor stage is “object permanence”—when the child knows that an object still exists after it is removed from sight. In the preoperational stage they can use symbols—they can think symbolically. This is where children really start utilizing their imagination. The concrete and formal operational stages are where most of education occurs—kindergarten through fifth or sixth grade. In the concrete operational stage of development, you have to attach very concrete situations, concrete examples, to new learning so that students can understand them. In the more formal operational stage, abstract thinking takes hold.

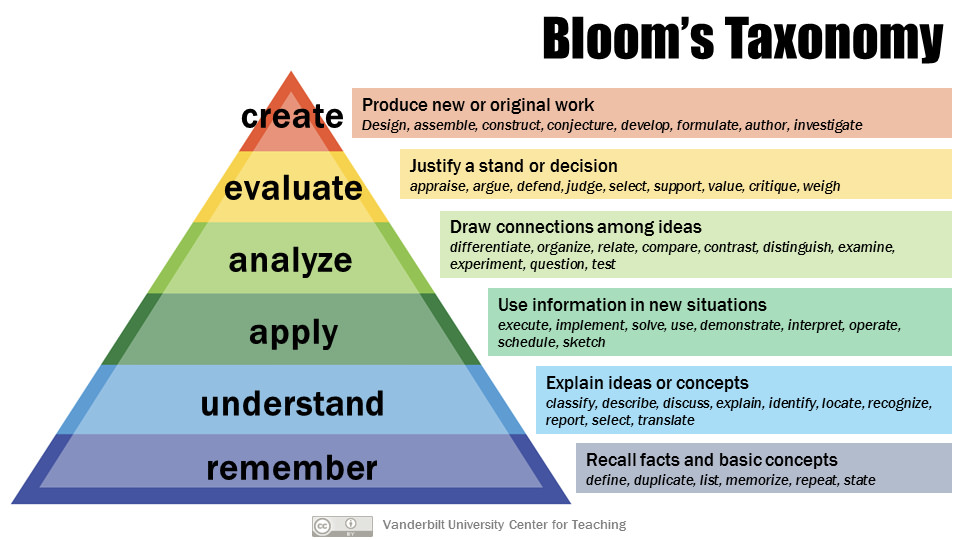

How is all that tied to our view of God? There’s no doubt that the concepts of God and grace are very abstract and thus the stage of development and understanding where education typically lies in those stages of development is important. Piaget’s work on the stages of development really led educators, in particular Benjamin Bloom and his colleagues to ask: What type of learning can students accomplish at different stages of their development? The question was answered in Bloom’s Taxonomy, a very education driven approach to understanding the level of thinking, the depth of knowledge a student needs going through the educational process.

The bottom of the pyramid is about remembering This is direct recall of facts. It is when a teacher asks students to direct recall facts and basic concepts. It’s the start of the process of building a knowledge base. From there the taxonomy move up in complexity. Can students be led to the understanding phase where they can actually explain, in their own words, ideas and concepts? Can they be moved into an application phase where they can actually take the knowledge and apply it to new situations? Can they be moved from there into an analyzing phase, and from there to an evaluating phase, and finally into the creative phase?

Bloom’s Taxonomy is the fundamental learning structure applied in education. Notice that the thought process changes from a concrete thought process to a much more abstract process. One of the difficulties in education that I think shapes how adults view God after going through the formal education process is the amount of learning that takes place in school. Typically, 80 to 90% of that learning actually takes place at that very bottom rung of Bloom’s Taxonomy, the knowledge recall base. I’m sure we’ve all experienced a lot of tests and quizzes where we were just regurgitating facts that we were told to know.

Did you really get to a level of understanding application analysis evaluation in your formalized evaluate in your formalized educational process? Research says you probably did not; that you may have gotten there somewhere between 10 to 20% of the time, but the educational process, the learning process in place today keeps students at the direct recall of knowledge stage.

So to relate this back to Michael’s question (how might our psychology introduce conflict and cause cognitive dissonance with how we view God, or how we should view God), fundamental to how we think to the psychology that we form, is how much opportunity we get to think abstractly as we’re moving through the educational process.

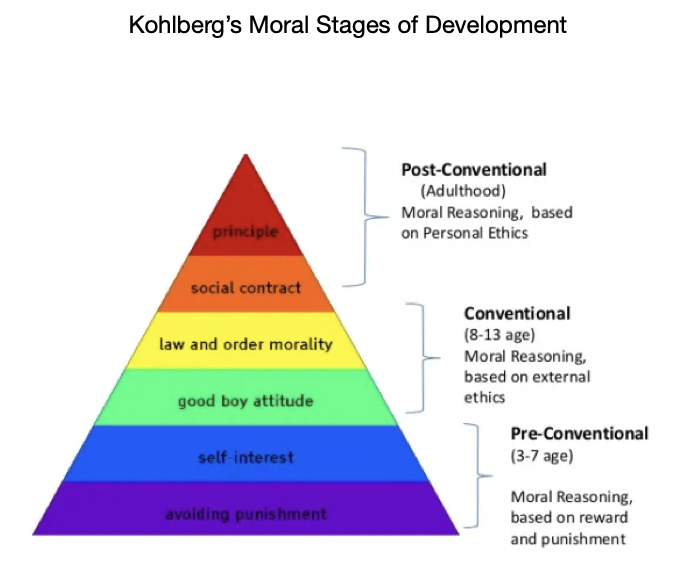

Based on Piaget’s work, Lawrence Kohlberg developed a Moral Stages of Development model. It is a little bit outside of education, but how we develop as moral beings seems pertinent to our discussion. In Kohlberg’s model you start at a place where you basically look at your morality through rules that are fixed and absolute. As with Piaget’s model, it is a very concrete basis. You then transition into judging actions according to your individual needs, then conforming to being nice (understanding that in society, you have to be nice), then to respecting authority, and finally, at the end, you are able to consider the individual rights of others. Again, the model goes from concrete to very abstract thinking.

However, the formalized educational process does not structure settings for the student to think in abstract ways. Unfortunately, the formalized education that all of us went through was very concrete. But whether we take the behavioral psychology approach, with rewards for positive behaviors and consequences for negative behaviors, or the developmental psychology approach, we move from very concrete thinking processes to very abstract thinking processes.

Can we know God through this behavioral psychology view? Is our understanding of God grounded in positive and negative reinforcements? Do we view God through positive and negative reinforcements or behavioral psychology? And if so, is grace God’s positive behavioral intervention and support system for humanity?

Can we know God? Can we see God in terms of developmental psychology? By hindering us from thinking abstractly does our education system make it difficult for us to see God? Is grace only understood when (if) we reach Piaget’s stage of formal operational thinking?

David: Last week we discussed the abstract concept, the metaphor, of being born again. At that first, infant, stage of life, good is what the infant likes and right is what the infant thinks. In the pre-teen stage, good is what mommy and daddy like and right is what mommy and daddy say is right. In the third (essentially teenage) stage, good is what your peer group likes and right is what the group says. In the final (essentially adult) stage good is what your society or your culture says is good and right is what society says is right. This seems to be a modification of Kohlberg, but I can’t recall the source.

Jay asked if we must go all the way up to Piaget’s late stages before we’re ready to accept grace. I would argue, going back to what Jesus says, that on the contrary: We must go back to stage one, the infant stage, where good is what I like and right is what I think. We must then assume that God is in the infant—otherwise how could it possibly unerringly know what is good and right?

It seems to me we grow God out of ourselves as we develop. Culture drums God out of us. I believe that’s what Jesus meant about being born again. As infants, we have only grace, and whatever happens is good and right.

Michael: Operational conditioning sounds very similar to how religion depicts God: If you’re good, you get good stuff; if you’re bad, you get diseases or other misfortunes. It seems a rudimentary way of looking at it. It doesn’t sound like how we should teach children. I don’t know much about education systems but I have the idea that some systems are trying to move away from that kind of conditioning, or at least to add more nuance to it.

Don: I presume that a teacher has a goal in mind when they’re teaching in a classroom—a lesson plan or a learning objective. Should a church, should a faith group have an objective in mind in terms of what view of God should be should be portrayed? We talked some weeks ago about the development of ChatGPTs specific to various faith groups—the Adventist Church is already working on it to make sure that the viewpoint that gets expressed by the Adventist AI is orthodox.

So I guess my question is, to what extent is a teacher’s rigid agenda necessary? Is it possible to educate someone in a more open format?

Donald: As I was completing my work in education, probably for the last 10 years, the Board of Higher Education described it as “learning outcomes.” You could miss getting accredited if you didn’t have learning outcomes properly put into position and learning outcomes.

It was confusing for educators, believe it or not, to determine the differences between what you want as an outcome for the class. Most of us would say, “OK, take our test, take the examples, do the lab.” That’s the learning outcome. Well, higher education won’t accept that. They want to know: “What are your specific goals? And are you meeting those? And by what methods do you get there?”

That was that was a real dilemma. I don’t know if it continues today. I went to many a conference regarding this, because I was the director of general education. It was imperative that institutions do this when the accreditation visits came.

All that being said, as an educator, as a teacher for 20 years, you have an intro class, which I think is pretty much that foundation level of data and information. If you don’t have the data and the information, it’s hard to get to any level of imagination. A couple of the best photographers I ever taught hated technology but loved photography. They didn’t want the data, they wanted to get to imagination, and in the end, because of who they were and what they were about, they were able to get there. But most students have to have that foundation and then build upon that.

My reason for saying all this is, can we agree on what the basic information is? The challenge for the learning outcomes for, let’s say, English 111 and 112, in a college setting, is that you have five teachers teaching it, you have multiple sections, and each teacher comes out of this a little different way. But higher education says, “No, we want the learning outcomes to be the same. I don’t care how you get there, but each in a different way. So can we agree?” In a sense, that’s what religions are. They’re trying to get you to the learning outcomes, if you will, to understand and know God. But they all work at it in a little bit different way. Think of the Amish and how they approach education.

Actually, as Don has said, Adventist education is amazing, because it really asks lots of questions and can undo some of the things that formal Adventism wants to have as a learning outcome. So can we agree upon that basic data? When we all of us come together and read Matthew, would we actually say we all agree on what the basic facts are? Because without that, how can we move along?

Is that a fair question? I don’t know. And I don’t think we necessarily do agree—we chat a lot. But I’m not sure that that we all agree upon the basic, fundamental essentials.

David: In some subjects, it’s easy to agree—in math, for example, it’s easy to set learning outcomes. We expect every student will have a full grasp of algebra, or whatever. But it becomes much more difficult with the humanities.

Jason mentioned conditioning people to do what is right. From a teacher’s perspective, the outcomes are a matter of answers that are prescribed and are not proscribed, rather than good or bad per se. We conflate what is good and what is right with what is prescribed and what is proscribed. What is prescribed is not necessarily good. What is proscribed is not necessarily bad. But that’s what we do. In the infant stage, there is neither prescription nor proscription, and that, according to Jesus, is the ideal stage.

Jay: Donald is suggesting that one of the ways that we see God is through the religious constructs that we belong to. Church has a high level of influence on the way we see God. How has the educational process, the psychology upon which education has been built, influenced religious constructs and religious structures?

If we go back to Bloom’s Taxonomy again, but instead of talking about education (remember I said education lives, probably 80 to 90% of the time at the remember/understand stage of Bloom’s Taxonomy) let’s let’s flip the question. If religion is a major component in our lives, if the religious structures of the world are major components of our lives and how we view God and how we view grace, then where do religious structures and constructs live?

I would propose that there is definitely a lot of recall: “This is your religion. These are the rules of your religion. These are the doctrines of your religion. Do you know what they are? Can you explain those to somebody else?” We definitely live in that realm. You might call it evangelism or you might call it indoctrination. Remembering is indoctrination. Understanding is evangelism. and applying application might be evangelism and application might be applying these things to your life.

So you now live a life of applications in your life based upon that religious construct. Does religious construct ever get into the analyze, evaluate and create phase? And if they don’t get there, but grace and God live up here, how do we ever get to a point where we can view God through a religious construct?

Donald: I think that’s absolutely fascinating, because does a church organization really want you to live up there? Do the church leaders want you to live up there? They may think in those realms, but some of us, including myself, would say we don’t have enough facts and information to live up there. I’m still down here, because I’m still trying to sort it all out.

Is that something that’s been imposed upon me. I don’t think churches necessarily want their flocks to move upwards. I think churches are pretty comfortable within the first three levels of the pyramid, and that’s where you feel good. I’m a good churchgoer. That’s where I live.

Because I taught photography I could easily have given an assignment and then just get all the images back and say, “This is a B, this is an A”, but a student doesn’t learn anything by that other than they think I think they did a good job, or I think they did a poor job. So early on, there were five things that are graded on every assignment, including Did they do what I asked? Because they could go out and do a great job that had nothing to do with the assignment. So how do you relate that to church organization?

Another two of the 5 grade points were for imagination of approach, and technical capacity. Sometimes they did a marvelous job on creativity but had no level of technical and then some came as bankers—they did everything mechanically, but they had no imagination.

So how does that fit within our faith? Where do we end? Is that personality? I’m not sure.

Michael: I think that’s the question Dr. Weaver was asking, which is: As a teacher, what is your objective? Is your objective to tell your students “This is what you need to know, this is what you need to learn” to try to get them to this creative stage. It’s hard to get somebody to the creative stage because you do have to go through all the stages and it’s usually much easier if there is an exam. If that’s how you will be judged as a student and as a teacher, just get them to learn the objectives and move along.

Jay: You just articulated the major dilemma that education finds itself grappling with. There’s no doubt that we live in those bottom two levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy for the very reason that you said: It’s hard as a teacher to develop lessons and opportunities for kids to analyze, evaluate and create Those are hard opportunities. Beyond that, they’re really hard to grade. Our educational system is driven by that. It’s very easy to grade something as right or wrong. If a student creates something, how do I the teacher evaluate it? Do I grade it as A, B, C, D, or F? We find ourselves in education living down there. That’s where we find ourselves being trained for basically our whole life. I would even say higher education lives down there. If I reflect on my higher education experiences, they’re living down there.

How can I ever get to a point where I can really view God or see God? I guess maybe the question is: Can you see God if you can’t analyze, evaluate and create? Is the picture of God more blurry when you’re only remembering and understanding and applying, as opposed to clear if you can analyze, evaluate and create?

Don: Jesus’s method of teaching, as we’ve said so many times before, is primarily one of interrogation—not of fact finding, but seeking to take them to a higher level. I’m wondering whether, in the parables and the questions that Jesus asked, he reaches some of the upper levels of that taxonomy that Jay just shared with us?

Donald: Reflecting on my classroom teaching, I recall that in 100-level classes sometimes I would not answer a student’s question directly; rather, I would say “Now that’s an interesting question.” Christ answered a lot of questions with questions. He didn’t respond with data, with the facts his interrogators wanted and thought they needed.

But typically, in a 100- or 200-level class the teacher is basically giving out information. But in 300- and 400-level classes the questions are different and so is the way the teacher answers: “Why did you ask that question?” This is especially true in the arts. It creates a dilemma for the teacher to justify an A or B grade to a student’s response. My policy was that an incredibly creative response, even though technically it failed, deserved a positive grade.

Sharon: I just began a 10-month series of integrating faith and learning with about 80 of our faculty members. We’re using George R. Knight’s 2016 book Educating for Eternity: A Seventh-day Adventist Philosophy of Education https://www.amazon.com/Educating-Eternity-Seventh-day-Adventist-Philosophy/dp/1940980127 as our text.

I’m wondering how we can integrate in that series the critical thinking component on the view of God. We socialize for an Adventist education, because we have a constituency that is paying more for a Seventh-Day Adventist education yet faculty are not integrating faith in the learning process. There seems to be a dilemma between admitting the need for critical thinking while maintaining some kind of boundaries and identity as an Adventist body.

Our branding requires us to have a common basis in knowledge—Bloom’s lower taxonomy. That is what creates our faith identity. It is hard for faculty to integrate that when many of them have never gone to “faith-enhanced”learning institutions. They are used to teaching raw science outside the value-added context of Adventist philosophy, or as George Knight puts it, “the epistemology of Adventist education.”

I think there is a role in Adventist education for that value-added Adventist philosophical context. After all, people are paying for that and not just for all the rote memorizing and passing the 28 fundamental beliefs quiz. But more than half of our students are non Adventist: We have Muslims, we have a lot of Catholic students, so we must seek an opportunity to let them ask complex questions about God without ignoring the fact that we are a “value-added faith environment” with an obligation to share the principles and the view of God through our Adventist identity.

Jay: Too often, I think, we view the upper levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy—the evaluating and creating levels—as a threat to our established brand. How is it that we as educators within a religious entity get membership to be able to think and act creatively without damaging the brand? Is that possible?

To me, it is one of the dilemmas we face and we tend not to go there. We are already programmed, in a way, not do that. How does that hinder how we view God?

Donald: What do our educational constituents expect of us as a Seventh-Day Adventist institution? I always felt pulled on that one. Students think they’re there because they (or, more often, their parents) are paying the bill and expect to get what they want. Why do they pay a considerable premium to go to an Adventist school if Adventism is presented by a teacher praying before class begins?

Religion is X amount of credits of Gen Ed in the context of a Seventh-Day Adventist environment whose value should not be underestimated. I really think constituencies more than that. Minimally, parents don’t want their kids hostile to Adventism when they leave the institution; they want them to love it, not leave it.

Sharon: I think that’s part of the reason why we really need a correct view of the image of God. We should not be looking only at the works—we should be sharing the actual love of God, I think the love of God is stronger than the threat of our doctrines and punishment for doctrinal transgressions. I really think that if you have genuine love, and you integrate that as Christ’s model of Adventism, I don’t think you really have a dilemma.

David: The elephant in the room—an enormous looming dilemma—is the future of education and religion in a world that is soon going to be taught by AI. There is no question in my mind that AI teachers will know more about the world, about any given subject matter, and about any given student—demographically, socially, economically, psychographically (you name it)—than any human teacher, Adventist or otherwise, could possibly hope to do. The AI teacher will also have more empathy, more understanding, and more knowledge of how to guide the student to meet learning objectives. (An interesting question is who will set those? The AI?)

My point is, that’s where the world is going. And if I were an Adventist education institution or indeed any educational institution, I would be asking such questions.

Donald: To Sharon’s point, I would say that the love of God as a learning outcome would be a very difficult thing. I think it can be done but can it be patterned in such a way that the Higher Learning Commission will accept it as an outcome. I really don’t think so, because I don’t think you can measure it. But students can measure it. They’ll know exactly where you stand as a teacher, over a period of time, if you integrate faith into your classroom. But I’m just saying it’s a very difficult thing to prescribe.

With regard to AI: How is AI any different than a great library? does it integrate the information in the books? We have a great library on campus, but it’s not enough just to go to the library—you need to go to class, too.

David: A library is just a haystack of information you use to search for a needle. AI can retrieve that needle much faster than you can.

Michael: The flip side of the coin of Jesus’ method of answering questions with question is it didn’t get him very far. He was not a very successful preacher in his own time, with few followers. He had 12 disciples who were confused most of the time and one of them sold him for just 30 pieces of silver. So it was a failure of the church or the movement in Jesus’ own time,

Is it different—is it possible—today? it seems to me it would be very hard. I would love to see it happen but I seriously question if it’s even possible.

David: I think Isaiah would say it’s the only way to teach about a God whose thoughts are not our thoughts, whose ways are not our ways. As the heavens are higher than the earth, so are his ways higher than our ways, and his thoughts higher than our thoughts.* (Isaiah 55:8-9)

Donald: Could there be a Higher Learning Commission to accredit churches based upon its constructs and outcomes? I think that’s really the fundamental question. Can it be done? Should it be done?

Jay: Bloom’s Taxonomy or even psychology would argue that a formalized system of attainment is antithetical to abstract thinking. Abstract thinking is the top of the pyramid. How do you formalize that? How do you formalize something that is not concrete? That seems to be part of the dilemma that we find ourselves running into.

To formalize something is to make it a very concrete thing or process, and the question I think we continue to struggle with is if God and grace, forgiveness, faith, love etc. are abstract concepts and not concrete things, should we even be trying to define them in concrete ways? How, how can we encourage and apply abstract thought processes to these kinds of things?

I agree with Michael that it does not seem possible, because of thousands of years of being programmed to not think that way. I think it is one of the major struggles that we find ourselves in.

Michael: I don’t think we can have an end goal for such an education and assert that abstract thinking will get you to one, because abstract thinking incorporates questions and whatever answers they suggest—no matter how strange and discomfiting—as part of the learning process.

Donald: The Higher Learning Commission seeks to stimulate critical thinking. Critical thinking was a common concept amongst faculty, but talking the talk is not the same as walking the walk. Higher education faculty tend to start thinking in particular patterns, and if you don’t fit their pattern, you are out.

How would critical thinking relate to our faith? Does the church really want me to be a critical thinker?

Reinhard: (Audio garbled)

Janelin: I think education really goes together with parenting, It’s 9 or 10 at night, so I’m super exhausted, and my 8-year-old asks me “Well, how do I believe in God?” That’s a really big question but I’m glad she’s asking such questions. I also want her to think about it because I want her to come to her own conclusion. It is part of her education, and part of parenting.

Don: Thank you, Jason, for leading the discussion. We’ll meet again next week.

* * *

* A benefit of editing these transcripts is that I can reconsider my own comments. In this instance, I misunderstood Michael’s question, so I have changed my answer accordingly. I said in class what he asked was not possible; in fact, I mean the opposite. —David

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.