What does “the separation of church and state” mean? How must the believer balance God and government? As noted last week, democratic government is neither self-derived nor self-sustaining. It is deeply rooted in Biblical principles of liberty and justice, but while not uniquely Christian, Christians do have a legitimate say in its preservation, given our devotion to the separation of church and state and specifically to the concept of religious freedom.

The so-called “Establishment clause” of the First Amendment to the US Constitution addresses the issue:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof;…

The phrase “separation of church and state” does not itself appear in the Constitution, but is attributed to Thomas Jefferson in a letter to the Danbury Baptists on Jan. 1. 1802. The relevant paragraph is:

Believing with you that religion is a matter which lies solely between Man & his God, that he owes account to none other for his faith or his worship, that the legitimate powers of government reach actions only, & not opinions, I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should “make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,” thus building a wall of separation between Church & State. Adhering to this expression of the supreme will of the nation in behalf of the rights of conscience, I shall see with sincere satisfaction the progress of those sentiments which tend to restore to man all his natural rights, convinced he has no natural right in opposition to his social duties. [Emphasis added]

What constitutes the church? What constitutes the state? What prerogatives do they hold over us?

The problem is that both religion and the state make great claims upon us as individuals: What we wear, eat, say, read, study, look at, respond to (and how we respond) and so on. Church and/or state regulate all these things and more. But what, when, how, and who we worship is not (in theory, at least) regulated by Western democratic governments.

Some other forms of government, however. intentionally and deliberately meld God and government. The civil law in Islamic states, for example, is underpinned by sharia law written hundreds of years ago for a culture and a time very different from ours today.

The story of Daniel underscores the collision of God and government and sheds light on the topic. It shows government seeking to re-educate Daniel and his companions into Babylonian ways. They were…

…youths in whom was no defect, who were good-looking, showing intelligence in every branch of wisdom, endowed with understanding and discerning knowledge, and who had ability for serving in the king’s court; and he ordered him to teach them the literature and language of the Chaldeans. The king appointed for them a daily ration from the king’s choice food and from the wine which he drank, and appointed that they should be educated three years, at the end of which they were to enter the king’s personal service. (Daniel 1:4-5)

Language, literature, history, cuisine, and education are all critical formative influences on young people; hence, government interest in using them for control. Daniel and his friends recognized that God also had an interest in these aspects, and chose God’s interests over governments. The ultimate test of paramount interest and control was this:

Nebuchadnezzar the king made an image of gold, the height of which was sixty cubits and its width six cubits; he set it up on the plain of Dura in the province of Babylon. Then Nebuchadnezzar the king sent word to assemble the satraps, the prefects and the governors, the counselors, the treasurers, the judges, the magistrates and all the rulers of the provinces to come to the dedication of the image that Nebuchadnezzar the king had set up. Then the satraps, the prefects and the governors, the counselors, the treasurers, the judges, the magistrates and all the rulers of the provinces were assembled for the dedication of the image that Nebuchadnezzar the king had set up; and they stood before the image that Nebuchadnezzar had set up. Then the herald loudly proclaimed: “To you the command is given, O peoples, nations and men of every language, that at the moment you hear the sound of the horn, flute, lyre, trigon, psaltery, bagpipe and all kinds of music, you are to fall down and worship the golden image that Nebuchadnezzar the king has set up. But whoever does not fall down and worship shall immediately be cast into the midst of a furnace of blazing fire.” Therefore at that time, when all the peoples heard the sound of the horn, flute, lyre, trigon, psaltery, bagpipe and all kinds of music, all the peoples, nations and men of every language fell down and worshiped the golden image that Nebuchadnezzar the king had set up. (Daniel 3:1-7)

The disparate cultural elements—the many kinds of music, peoples, nations, and languages—that hitherto had prevented Babylon from becoming a single, unitary people were now to be unified through the imposition of religion. But Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego refused to accept the new religion:

Then Nebuchadnezzar in rage and anger gave orders to bring Shadrach, Meshach and Abed-nego; then these men were brought before the king. Nebuchadnezzar responded and said to them, “Is it true, Shadrach, Meshach and Abed-nego, that you do not serve my gods or worship the golden image that I have set up? Now if you are ready, at the moment you hear the sound of the horn, flute, lyre, trigon, psaltery and bagpipe and all kinds of music, to fall down and worship the image that I have made, very well. But if you do not worship, you will immediately be cast into the midst of a furnace of blazing fire; and what god is there who can deliver you out of my hands?”

Shadrach, Meshach and Abed-nego replied to the king, “O Nebuchadnezzar, we do not need to give you an answer concerning this matter. If it be so, our God whom we serve is able to deliver us from the furnace of blazing fire; and He will deliver us out of your hand, O king. But even if He does not, let it be known to you, O king, that we are not going to serve your gods or worship the golden image that you have set up.” (Daniel 3:13-18)

This passage focuses on the where, how, and what of worship. The key elements of controlling worship are identifiable as:

- Assembling the masses, using mob mentality to control behavior at scale. This was not just any mob: It was an assembly of the rich, powerful, intellectual—the influential people of Babylon.

- Entertaining them: Music was mentioned four times, in great detail, in the passage. Entertainment was a tool of control.

Today, Christianity, with 2.3 billion followers worldwide, and Islam, with 1.8 billion, have diametrically opposite views concerning “God and government”. But since Constantine made Christianity the official religion of the Roman Empire in the 4th century AD, Christianity has not always been in favor of the separation of church and state. Through the Dark Ages and even into the Reformation, the Church tended to oppress. It was not until after the Enlightenment of the 17th century in Europe and even into the 19th century, as evidenced by the flight of religiously oppressed pilgrims to America, that the separation of church and state really began to take hold.

Mutual back-scratching by government and religions to control the masses is as old as history. Even today, Islam recognizes no separation. Sharia law is rooted in the concept that good government depends upon Allah and His messenger the prophet Mohammed, and that all law can be derived from the Qur’an. Even in America, even today, some Christians advocate that the law should be based on godly principles extracted from the Bible.

What should believers wish, work, and fight for? Should we fight for God-fearing regulations influenced and underwritten by religion? Or should we fight for separation of church and state? It brings us back to the question: What belongs to God and what belongs to Caesar? What does Daniel teach us? How can the laws of God or Allah (or whatever name we give Him) be understood to inform jurisprudence today? Is it even reasonable? Must we again stone Sabbath-breakers? Must we sever the hands of thieves? Are laws timeless and immutable? Are they culture-bound? Can Scripture—Bible, Qur’an, etc.—be the basis for modern and postmodern law? Again, what does Daniel teach us?

Donald: We talk of achieving unity with diversity, but what we probably really want is for everyone else to be like us—to share our culture. We tend to oppose government initiatives that counter this want. It explains why Republicans and Democrats are worlds apart.

David: They are worlds apart in mundane matters, but not necessarily in more fundamental matters. Confucius taught five virtues* that all the people—including the Emperor—should have, regardless of factions and politics: Gravity, generosity of soul, sincerity, earnestness, and kindness. If church and state, religious leaders and followers, emperor and subjects, all possess these same virtues, then there is no problem rendering unto God and Caesar because both should value and expect benevolence, charity, and humanity. Taxes and other things are quite outside the discussion.

Donald: These virtues appear to be lacking, with regard to the current refugee situation at the border with Mexico.

Dr. Singh: The Bible has many verses on government and Christians. Christians must care about politics because it affects our culture and society. In the Old Testament, the Lord keeps an eye on everything that goes on in this world, no matter who is ruling.

Submit yourselves for the Lord’s sake to every human institution, whether to a king as the one in authority, or to governors as sent by him for the punishment of evildoers and the praise of those who do right. (1 Peter 2:13-14)

Don: But what if the human institution is a bad institution?

Jay: We think in linear terms. We have texts that say God installs and removes some leaders and we tend to apply that assumption to all leadership. So when leaders do ungodly things, we don’t feel obliged to follow them. This was the case with the three Hebrew worthies, whose stance was vindicated by their divine rescue from the fiery furnace. The problem is that the sequential logic of this story does not usually apply in life, but our linear thinking biases us to assume it does. We want to see the hand of God in everything, thinking that by so doing, we can understand God’s plan. But that is dangerous territory.

David: Christians and Moslems are not alone in thinking that godly principles should underpin government. It is a universal belief. The Chinese have believed throughout most of their history in the principle of the mandate of heaven which bestows legitimacy on an emperor or empress only as long as s/he is just. China has never had much in the way of an organized central religion—its folk religion and the Buddhism it borrowed from India never had or sought secular powers—yet the Chinese acknowledge virtues nearly all of us acknowledge to be of divine origin.

In China, bad government would inevitably lose the mandate of heaven, and the dynasty would fall and be replaced. Bad government was not ungodly government, it was simply government that oppressed or otherwise failed the people. Dynasties were overthrown not for religious reasons, but for secular reasons. However, those secular reasons have a common, universal, divine component called Confucian virtues in China and godly principles by us. Whatever we call them, they are virtues that unite all of humanity.

Kiran: We ascribe to God things we don’t understand. Fire and earthquakes were once in that category. Anything too complex for us to grasp must be divine, we think. To commoners, becoming king was so inconceivable it had to have a divine origin. But this is not God’s kingdom—it is Satan’s kingdom, because of Adam. God is doing His best to contain the situation so that we have a chance to listen to His promptings and receive His acts of grace, until the time when His kingdom comes. No ruler is God’s. They are permitted by Him (like Saul, for example) but not chosen by Him. Our obligation is to preserve life by following social rules of order. In North Korea, it means bowing down to the Kim family dynasty. North Koreans do not get to walk away from the Kims’ fiery furnace.

Dr. Singh: In Hindu philosophy, God is everywhere, but in Christianity, He is not; it is Satan who is everywhere. The spirit will be there wherever two or three gather in His name, but if God were everywhere on earth, earth would be heaven. There would be no murders with God present. Hindus worship rocks, trees, and animals because they believe God is resting in them. Nature is the art of God. It helps us to remember Him and praise His creation, but He is not everywhere in it.

Donald: We think of God as omnipresent.

David: To me, that omnipresence takes the form of the inner light, the holy spirit. The problem is that we suppress it—we “hide it under a bushel”, as the Bible puts it. To the extent we suppress it, then to all practical intents and purposes perhaps God might as well not be there; but He is.

Jay: The opposing viewpoint is that sin cannot exist in God’s presence… and He is always present in heaven. We are in a gray area where God is partly present, which explains our dilemma in rendering to Him and to Caesar. The “render” statement is wrapped up in the possessive: God and Caesar each own some things that we are holding—in Caesar’s case, they are such things as coins with Caesar’s likeness stamped on them. But things are not always stamped so clearly, and when that is the case (as it usually is), the more definite we are in apportioning ownership, the greater the risk of being wrong. God warns us against being too sure of ourselves in understanding Him.

Donald: We each seem to want to know our place in history; to understand who we are, why we exist, and who God is. It is an egocentric need, hard to shake off.

Jay: This is true especially if we are trying to establish our own importance, or the rightness or correctness of our position.

Donald: A God who sees every sparrow presumably values each of us highly as individuals. But He may not necessarily value us collectively, as a society.

Kiran: Would Daniel have become as important as he did if Babylonian aggression had not put him in an awful, anti-religious place where he could stand up and be noticed? Would we even have heard of him? We can’t define, based on our own understanding, whether a kingdom is conducive to a good spiritual life or not. I might be a better Adventist if I were in a place where I am constantly challenged and there is something in me that wants to prove that I am better. But I might be a weak Adventist there too, because no-one is looking and I can do whatever I want. Whatever the state of a society, grace is there to cover us. Where there is more sin, there is more grace.

Dr. Singh: I was part of a successful Adventist anti-smoking campaign in India. Because we had acquired good publicity, a politician asked us to endorse his party. We refused, and he was very angry, but politicking was not our business.

David: That’s a good example of the proper separation of church business and state business. But I wonder if our attempt to differentiate them is too legalistic. We make the whole thing sound like a property rights lawsuit. Law is a human construct. It surely does not apply in the spiritual realm. We are never going to be able adequately to define what is God’s and what is Caesar’s, but we may know it when we see it—as in the example Dr. Singh just gave us.

Don: If we compare the relationship between God and Islamic government (Iran’s for instance) with the relationship between God and Western democratic government, can we honestly assert that God prefers one over the other? Does God prefer theocracy—the form of government He established for ancient Israel? Did we so corrupt that (possibly ideal, from God’s perspective) form of government so much that we had to separate God and government, church and state?

David: I think Jesus was telling us in the “render” statement that worldly government is of no concern to God; that He is not against our efforts to maintain social order but that that is Caesar’s business. He was telling us, I think, that we do know the difference. It seems to me He was hinting that even if it were definable (which it is not) there would still be no need to define it. As in the example cited by Dr. Singh, we know it when we see it.

Donald: I am concerned that we are using words too carelessly. We conflate God, religion, and church on the one hand, and government, state, Caesar, and now politics on the other. If we are being legalistic, does that mean we are coming out on the side of government rather than God?

David: To me, yes. Good point. I would not use the word legal in the same context as God (look where that got Job). It’s a human construct that is only necessary in a Fallen world. Heaven, being sinless by definition, has no need for law or for government, for that matter. The notion of a post-apocalyptic paradise on earth “governed” by 144,000 anointed bureaucrats in heaven is ludicrous, to me. What’s to govern? “Paradise” just doesn’t go with “government”!

Donald: It was not “illegal” to eat from the trees in the garden of Eden. We needed the Ten Commandments only after the Fall.

Jay: If the Ten Commandments—God’s law—were necessary only because of sin, because of the Fall, then even they may be more about the government of Man and rendering to Caesar than about God and rendering to Him. The things that only God must own, because He “coined” them (and which Man must therefore render to Him) are things such as life itself, love, forgiveness, grace. Everything else is of no interest to God.

Donald: Do they include the five virtues described by Confucius?

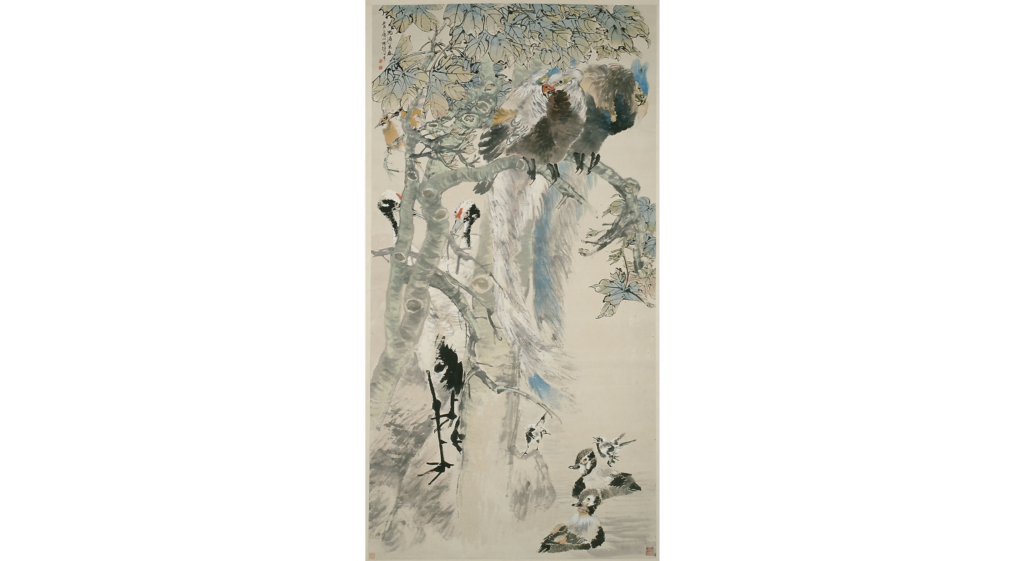

The Five Virtues

Qing dynasty (1644–1911), 1895

Ren Yi [zi Bonian]

1840-1895

This is NOT about the five virtues discussed in the text—it is about the Neo-Confucian Five Cardinal Relationships. But it’s a beautiful picture, so… 🙂 —Ed.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.