Grace is one of the great mysteries of God. The widespread, ubiquitous reach of grace is manifest in God’s being the God of all mankind. And as we’ve been discussing this past few weeks, it has a mysterious transforming quality as well. We are changed, Paul says, by grace, in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye.

We usually speak of grace in the context of grace for the lost, the sinner, the outcast, the rejected, the broken-down and broken-hearted soul. But we must not underestimate the power and the reach of grace. Grace is for the good as well. So even if you’re good—even very, very good—you need grace as much as the next man or woman.

Last week we mentioned the story of Nicodemus, where we see that grace is for the good as well.

Now there was a man of the Pharisees, named Nicodemus, a ruler of the Jews; this man came to Jesus at night and said to Him, “Rabbi, we know that You have come from God as a teacher; for no one can do these signs that You do unless God is with him.” Jesus responded and said to him, “Truly, truly, I say to you, unless someone is born again he cannot see the kingdom of God.”

“For God so loved the world, that He gave His only Son, so that everyone who believes in Him will not perish, but have eternal life.”

Nicodemus said to Him, “How can a person be born when he is old? He cannot enter his mother’s womb a second time and be born, can he?” Jesus answered, “Truly, truly, I say to you, unless someone is born of water and the Spirit, he cannot enter the kingdom of God. That which has been born of the flesh is flesh, and that which has been born of the Spirit is spirit. Do not be amazed that I said to you, ‘You must be born again.’ The wind blows where it wishes, and you hear the sound of it, but you do not know where it is coming from and where it is going; so is everyone who has been born of the Spirit.”

Nicodemus responded and said to Him, “How can these things be?” Jesus answered and said to him, “You are the teacher of Israel, and yet you do not understand these things? Truly, truly, I say to you, we speak of what we know and testify of what we have seen, and you people do not accept our testimony. If I told you earthly things and you do not believe, how will you believe if I tell you heavenly things? No one has ascended into heaven, except He who descended from heaven: the Son of Man. And just as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of Man be lifted up, so that everyone who believes will have eternal life in Him. (John 3:1-16)

Nicodemus is good; very, very good. He’s a Jew of the Jews, a Pharisee, a leader and a teacher of Israel. It seems that he’s coming to Jesus to understand more fully Jesus’ mission, seeking to find more of the backstory to the miraculous mission of Jesus that he’s witnessing. He is taken aback by Jesus reversal of the tables and the call for this good, righteous, educated and upstanding leader to have a complete do-over. “You must be born again” takes him by surprise. He doesn’t understand it. With all of his education, he doesn’t understand what Jesus is talking about.

Spiritual rebirth is the product of grace. It is to start over back to the beginning, relearn everything. Nicodemus’ education needs, Jesus says, a complete redo. “Relearn your spiritual habits, relearn your spiritual practices, relearn your spiritual outlook, relearn your spiritual beliefs, your long held concepts, and relearn your picture of God.” That is what grace does.

In using the metaphor of rebirth we see that who we are does not change—that is to say, our DNA and rebirth does not change. But what we are becomes widely and utterly different. Rebirth, spiritual rebirth, still leaves us as the son or daughter we were before, but now with a completely new spiritual outlook. Grace changes everything.

Jesus then goes on to illustrate the transforming power of grace by referring to a story familiar to any Jew (verse 14): “And just as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of Man be lifted up,…” This is the story of the bronze serpent in the wilderness. The road from Egypt to Canaan is the metaphorical road of life. The road of life is through the wilderness, a dry and desolate place. It is a road, however, full of God’s grace. God underwrites the trip, in reality and figuratively, beginning with the plundering of the Egyptian jewelry to begin the trip. Manna is a symbol of grace, as well as water from the rock, the pillar of cloud by day, the pillar of fire by night. And don’t forget about the quail that came down for the non-vegetarians.

Here is the story:

Then they set out from Mount Hor by the way of the Red Sea, to go around the land of Edom; and the people became impatient because of the journey. So the people spoke against God and Moses: “Why have you brought us up from Egypt to die in the wilderness? For there is no food and no water, and we are disgusted with this miserable food.”

Then the Lord sent fiery serpents among the people and they bit the people, so that many people of Israel died. So the people came to Moses and said, “We have sinned, because we have spoken against the Lord and against you; intercede with the Lord, that He will remove the serpents from us.” And Moses interceded for the people. Then the Lord said to Moses, “Make a fiery serpent, and put it on a flag pole; and it shall come about, that everyone who is bitten, and looks at it, will live.” So Moses made a bronze serpent and put it on the flag pole; and it came about, that if a serpent bit someone, and he looked at the bronze serpent, he lived. (Numbers 21:4-9)

Water from the rock and manna had become detestable. They rejected the very elements that define God’s grace. But rejection of God’s grace has fiery and fatal consequences, visualized here as venomous snakes. This is the condition of mankind apart from grace, a pit of deadly, poisonous vipers. The remedy is a return to grace.

Here we see what Jesus was alluding to with Nicodemus: A bronze serpent on a pole (really a bronze serpent on a cross—the symbol of grace). Jesus said that Nicodemus would be lifted up as Moses lifted up this serpent in the wilderness. And notice what was required of the bitten in Numbers 21:9: Anyone who was bitten could look at it and live. This is the price of grace: Look—don’t turn away—and you will live. No statement of belief is required. There is no ritual to perform, no work to do. Just look, if onlya fleeting glance. The only thing that limits grace is to turn away from it. Jesus says that the bronze serpent is himself, the true and everlasting symbol of grace. The symbol of a snake on a pole has become a universal symbol of healing. It is even today often seen in in medical emblems.

The fact that it was made of bronze is, I think, significant as well. The metal alloy bronze is frequently mentioned in the Bible. It is the metal of the common man. Its special use is recorded in the making of the wilderness sanctuary and also in the making of Solomon’s temple, where it was used for furniture and implements in the outer court, in contrast to the most holy place where the furniture was made of gold.

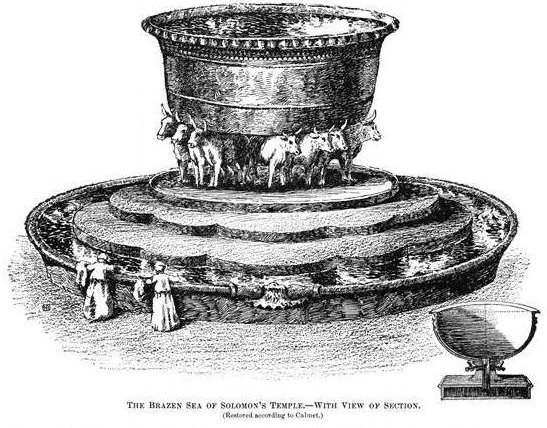

The bronze furniture is in the outer court—the court of the common man. Here was the bronze altar, the altar of sacrifice, the place for the furnishing of blood, and also the bronze laver (wash basin) on the back of 12 bronze oxen. This great bronze tank, sometimes referred to as “the molten sea,” is used for ceremonial cleansing.

Blood and water, both of bronze, the symbols of cleansing, the symbol of grace. In John 19, verse 24. It speaks of blood and water coming from Jesus after his death, the ultimate grace. When they came to Jesus, John writes in 19:24, and found that he was already dead, they did not break his legs. Instead, one of the soldiers pierced Jesus’s side with a spear, bringing a sudden flow of blood and water.

The bronze serpent became grace personified—life-saving grace. So highly valued was this bronze serpent by the Israelites that it became, over time, a highly valued symbol of veneration. Eight hundred years later the bronze serpent was still around. We find the bronze serpent in this passage (“He” refers to Hezekiah, the good King0:

He did what was right in the sight of the Lord, in accordance with everything that his father David had done. He removed the high places and smashed the memorial stones to pieces, and cut down the Asherah. He also crushed to pieces the bronze serpent that Moses had made, for until those days the sons of Israel had been burning incense to it; and it was called Nehushtan. (2 Kings 18:3-4)

Hezekiah breaks down the bronze serpent, now more than 800 years old, because it had become, in fact, an idol. The very symbol of God’s grace itself became an object of veneration. Instead of pointing to something, it became an object of worship. A symbol had become an object. Grace had become works. This is the condition of fallen man. We seek to objectify grace. We make crosses of gold and hang them from chains around our neck like a talisman. We venerate the shroud of Jesus. We burn candles in front of relics—teeth and bones.

David Farley wrote:

A quiet groundswell of Catholics will not give up the time honored tradition of praying to a saints bodily remains. Pope Benedict the 16th reinstated the Latin mass, so why not bring back an emphasis on relic veneration as well?

Here is his article in full:

The Bone Collectors: It’s time to bring relics back to the Catholic Church.

BY DAVID FARLEY

OCT 20, 200912:08 PM

Catholic relics are gaining popularity:Some believe that listening to heavy metal and soaking in its sometimes faux macabre culture can lead to the devil. It led me instead to a fascination with holy relics. I was perhaps the only teenager in my suburban Los Angeles town who yearned to see bones and other pieces of sanctified stiffs encased in glass. That was what drew me to ask an ancient woman at my Catholic church’s administration office what relic was housed in the church’s altar—a simple question, I thought. She admitted that not only had she never been asked that question, but she had no idea and called in Father Dennis. He was equally in the dark. :

Which was a little bit strange to me. After all, these spiritual accoutrements were a large part of the Catholic experience for well over a millennium. But a quiet groundswell of Catholics won’t give up this time-honored tradition of praying to a saint’s bodily remain. Pope Benedict XVI reinstated the Latin Mass. So why not bring back an emphasis on relic veneration as well? A French priest is currently touring the United States with the supposed bones of Mary Magdalene, and the faithful are flocking to pray in front of them. In September and October, the relics of a 19th-century nun, St. Therese of Lisieux, went on a 28-stop tour around Great Britain. If the thousands of devotees who came to witness these lovely bones are any indication, the faithful are hungering for a less sterile form of religion. :

While there’s no scholarly consensus on when relic veneration began, many historians point to the year 156 A.D. and the death of Polycarp, then bishop of Smyrna (in modern-day Turkey). He got on the Romans’ bad side by praying to Jesus instead of the Roman gods, and he was burned. After the pyre cooled, Polycarp’s followers scurried over and scooped up his remains and ran off with them. With that, the cult of relics was born. :

Relics became ingrained in Catholic Church orthodoxy at the Second Council of Nicaea in 787, when church authorities passed a law stating that every church should have a relic at its altar. The punishment for failing to obey: excommunication. But ever since the reforms of Vatican II in the early 1960s, relic veneration has virtually disappeared from the official landscape of Catholicism, particularly in the United States. Relics weren’t actually mentioned during the three-year council, but church leaders did address the way new churches should be designed. By the time Vatican II was over, iconography was out, in favor of a lighter, more airy atmosphere, uncluttered by images and, apparently, relics. If that wasn’t enough, in 1969, the church officially laid to rest the 787 ruling at Nicaea by no longer requiring Catholic churches to posses a holy remnant at their altars. :

The buying and selling of relics—called simony—is technically forbidden under church law, but if you can overlook that law, you can start your very own DIY relics collection at A.R. Broomer Ltd., a tiny antiques shop in New York City. Amanda Broomer’s shop is crammed with two types of objects: 19th-century wooden santos dolls and holy relics. Broomer, who is Jewish and has no spiritual connection to the curios, is motivated by the beauty of the reliquaries. “I told my parents that if the Jewish faith made things this visually appealing, I’d be selling those, too.” The shop shelves are lined with small containers holding a shard of bone, a flake of skin, or a strand of hair. Many of the relics she receives come straight from churches that have been closed. After having no takers with other parishes, some church officials feel they have no other option but to send someone over to Broomer with a load of relics in the hope that they end up in the right hands. :

So how much does a piece of a pious person run you these days? It all depends on official papers of authenticity and/or an official red wax papal seal, both of which mean a relics expert at the Vatican has inspected the piece and decided it is the real deal. Without one of these, a relic’s price can drop. During one of my visits to Broomer’s shop, I spotted the vertebrae of St. Redempta, a sixth-century martyr, with papers and a papal wax seal; it goes for $2,500. Next to that was a bone shard of St. Patrick (without papers), priced to sell at $495. And yet next to that was a piece of flesh from Pope Pius X with papers: $350. :

Broomer’s relics usually come primarily from obscure saints—especially early martyrs—because they’re more likely to be authentic. The superstar saints—St. Francis of Assisi, St. Catherine of Siena—are the most counterfeited. But that doesn’t mean pious pieces of the most precious individuals in Christianity haven’t come through her door: the Virgin Mary’s breast milk, baby Jesus’ swaddling clothes, a thorn from the Crown of Thorns, a sliver of wood from Christ’s manger, a strand of the Virgin Mary’s hair, Joseph’s walking stick, and various parts of the Apostles. :

Relics are not just body parts. Saints also had possessions. They wore clothes and jewelry. They touched things. Eventually, the Catholic Church put in place a system for classifying relics: A first-class relic was a body part of a saint; a second-class relic was a saint’s possession; a third-class relic was an object that had touched a first-class relic; and a fourth-class relic—the least valuable but the easiest to produce—was an object that had touched a second-class relic. :

Though holy relics may still have their place in modern spirituality, they represent a time when saints were posthumous medieval rock stars, pilgrims their devout groupies and monks their roadies. In medieval Europe, the quest for salvation pervaded every breath and movement and thought of the devout. For the faithful, praying to a saint’s relic was like a direct line to saints who acted as intercessors for God, VIP residents of heaven who could cause miracles and help prayers be answered. The faithful often prayed at saints’ tombs or in front of their relics displayed inside churches. But there were also private relic collections in the Middle Ages. Charlemagne, as pious as he was powerful, had a vast collection of relics (including, some say, the holy foreskin). Charles IV, the 14th-century Holy Roman emperor, held an annual relics show at his home base in Prague to show off his collection of curios (of which the pièce de résistance was the breast of Mary Magdalene). A couple of centuries later, Renaissance Prince Albrecht of Brandenburg had a stock of saintly remains so huge that a tireless pilgrim could have accrued a remission from purgatory of 39,245,120 years. :

Today Broomer has a roster of regular clients, many of whom are not princes or potentates; they’re mostly middle class, male, and gay. Some attended seminary before they dropped out of the church or were intentionally scorned. Others belong to the clergy or are officially connected to the church. :

One of those clients in the latter category is the Rev. Paul Halovatch, a chaplain in Connecticut, who has been collecting relics for 30 years. Among his 100 or so holy curios are a piece of the post Christ was whipped on, a chunk of Christ’s crib, and 10 pieces of the True Cross. He’ll bring out a relic of a saint on that saint’s feast day and bless people. He purchases relics from Broomer in an attempt to “rescue” them from falling into the wrong hands, which he claims they can easily do. :

Perhaps churches will stop shedding their collections—and start building them back up. One small church in Iowa, St. Donatus, recently moved a relic from the church museum to an altar in a side chapel in the church, back in the place where it was originally intended. Which means there’s at least one church I can now walk into and ask what relic they have at the altar, and I’ll get more than just a shrug.

(https://slate.com/human-interest/2009/10/it-s-time-to-bring-relics-back-to-the-catholic-church.html)

“But,” you protest, “I don’t worship relics!” Those of us who don’t worship relics make idols of other things—idols of our doctrine, idols of our belief, even idols of our Bible. We worship what we can see, what we can feel, and what we can comprehend. For example, the Sabbath: Like a bronze serpent, we’re at risk for idolizing when we make this powerful symbol of grace into a display of what we do or what we don’t do on the Sabbath.

When we make what we do the center of our Sabbath we, as it were, burn incense to the Sabbath. We objectify the Sabbath and turn our back on this powerful symbol of grace. That’s why Jesus says even those of us who consider ourselves good must be born again. We need a reboot of our spiritual operating system. We need to restart a renewal of what grace means and what grace does.

Why do we seek to objectify grace? Why is worship so directly tied to things—relics and rituals, doctrines and demeanor? How can we be spiritually born again? How can we relearn? How can we re-understand our doctrines so that we might experience that reboot of our spiritual thinking? Religion is so filled with what we do— rituals and routines—or how and what we sing (we can sing lively, but not with too much beat) or how we pray, or what we read—which translations that we read from. And we really should read from a leather-bound Bible. We should not read it on our iPhone. There is something not right about that, we think.

When I was a boy, the Bible had a very special place in our home. You would never put the Bible in a bookshelf like like a regular book on its edge. You laid it flat on some important place in the home and made sure that nothing, nothing at all, ever got on top of the Bible. We also venerate baptism, full immersion, no sprinkling. Our communion service and foot-washing, veneration of our Little Red Book, veneration not of relics, but veneration of rituals.

How does special rebirth take place? Can we have worship without relics? Can we have worship without rituals? Do we really need them? Maybe we just can’t live without them. Jesus, after all, gave us rituals. He underwent baptism, he gave us an illustration of foot-washing at the Lord’s Supper.

How does grace operate in worship? What are your thoughts today about ritual, relics, and grace? Our worship is so often centered on me and what I do. But grace is centered on God and what he does. Is it even possible that fallen man can practice a religion centered on God?

C-J: Sorry guys, but grace to me is like the air we breathe, you can’t see it. You only know when it moves so that you feel it. But without it, we die. And ritual is a way of focusing, drawing our attention, and making it singular. There is a lot of clutter in our lives. And relics, I think are like using a crutch: They support us. They’re tangible. They’re very three dimensional, where we live. And I believe that’s a structure of what God meets us where we are.

There are days we need to hold the Bible and read it slowly and meditatively. That’s a relic. It’s been passed down for 1000s of years, through oral traditions and then in the written word. Ritual is usually done in private or in community. And it focuses us. And grace is ethereal. We die without it. But somewhere in the other two, the ethereal is expected to manifest itself.

David: I’ve been quiet for a few sessions because I still have a fundamental problem with how we’re defining grace. As I understand the passage from Numbers, it is an allegory of the road to life, but here I think “life” means eternal life. The Promised Land is not an earthly land, it’s heaven, it’s eternity. That’s what grace provides. It seems to me does not make any difference to you here on earth except at the transition from mortal life, through death, into eternal life.

Such grace is universal. Everybody on the planet, maybe everybody in the universe, dies. It is certainly a great mystery, a great fear, a great unknown. We certainly can influence whether or not we’re receptive to that grace, even at the point of death. You can reject it and thereby imperil your very soul. But we keep returning to the idea that grace is something that happens throughout mortal life and makes that life better. I just don’t see that.

Don: If that theory is correct, then grace would have no effect on our worship here and now.

David: Correct.

C-J: I think grace has a great deal to do with our worship and the choices we make. It’s a an intervention. I have seen many times what I call grace, when there’s conflict, and it seems like God softens the heart and holds the hand and a different choice is made. That is grace. Or when I’m when I’m feeling very isolated, and it’s just me and God, and it seems like he always makes provision. Always. It’s not just the food on my table; it’s a phone call that brings a smile to my face. I think God is in everything, the sun that rises, and that is grace for me. It brings a peace, it brings hope. It allows me to forgive. It’s nothing that I can do of myself. I see grace everywhere.

David: What do you worship? To me, to appreciate the sun shining is true worship. Acknowledging the goodness around you is worship. The notion of going to church or synagogue to pray is not real worship. It’s not what God wants. God wants you to worship internally. People who have never heard of Jesus or have never been subjected to any religion can and do worship in their own (true) way. They have that presence inside them—that thing that can make them feel good or steer them away from doing something they shouldn’t do.

If you want to call that grace, that’s fine. It’s the Holy Spirit acting upon every man and woman. But worship is another matter, and I take issue with it because I think we don’t focus nearly enough on the internal worship that takes place in every human being. We focus too much on the narrow worship that takes place in institutions of religion.

Don: Jesus might agree with you. He said to the woman at the well that God is a spirit and those that worship him must worship him in spirit and in truth.

Michael: I agree about death, but what type of death? The word eternal might be tripping us up because in the traditional sense of the word, being eternal means that after you die physically, you rise up as an eternal being. To me, as a scientist, that doesn’t make any sense. It just doesn’t. There is no reason for me to believe it. But that doesn’t mean that I don’t have to believe or think or have faith in being an eternal person. And so in that sense, grace can help me die and become eternal.

But what does that mean? If I have to define it, it means the death of my ego, my selfishness, my self-focus, and helps me put the emphasis and the focus on God instead. So that might be where grace leads to death and then resurrection. It is a personal transformation.

Don: Do you see that as being anything like what Jesus meant by being born again?

Michael: I think that’s what I’m seeing.

C-J: For me, worship is about community. When I would worship in any congregation, but especially in a large congregation of spirit-filled people, I lost any sense of myself and I felt this huge energy, literally, of the presence of the Divine. The songs were worshiping God. But it was transformative. I just felt literally filled with this energy and light and understanding spiritually of what was transpiring. And I felt the same way when I was water-baptized, I think it’s about community and oneness, this incredible thing that happens in the singularity.

Donald: I’d like to talk about relics and how we go about doing spiritual matters. I have a number of things in my home that were my parents’ or my grandparents’ things once. It’s not that they have monetary value but they just make me feel still connected. They were meaningful to them, and even though they are gone, I can still connect to them.

Spiritual matters are a challenge because all of it is just conversation, but we want to make it real. As human beings, unfortunately, we start really organizing spiritual matters—that is, we build doctrine. We build churches, we build places, we build things, and we have rituals and obligations. I see that not as bad per se; it’s just the way human beings go about doing it. We can’t just leave it at the spiritual level, we want to make it real, and we do that by putting things in boxes.

Reinhard: Relics are parts of history. If we look back through the Bible, the bronze serpent illustrates the presence of grace in biblical times. Relics teach us that grace was present in the past, is present now, and will be there in the future. To me, grace is the guiding light for us in this life. We study knowledge in formal institutions. Education is a lifetime process. So too in our spiritual education: Grace was, is, and always will be present to guide us in life.

We have to make adjustments, we have to modify our priorities in terms of our spiritual growth, like Nicodemus when Jesus told him about being born again. We have to make adjustments in our attitudes for our spiritual growth, in order to keep adding to and refreshing our relationship with God.

To me, worship is part of the process. We worship as individuals and as a collective group. Both are important. But the goal of worship, the most important thing, is to connect with God in our life. We won’t worry about the future as long as we stay attached to him, as long as we keep God as our priority. That is what he wants in our life until the end. All we need to know is that grace is always going to be present as it always has been in the past, and we will be strengthened and won’t have to worry about what we’re going to face in life.

Anonymous: Sometimes I think I’m worshiping my Bible, because I spend a long time reading it and I enjoy it. I don’t know if my attachment to the Bible could be seen in a positive way or a negative way. But to be attached that much to something is maybe not the right way. I don’t know. But without the Bible, I wouldn’t have known grace and I wouldn’t experience God at first hand. It’s such a priority for me that I sometimes neglect my chores. I just keep reading and ignoring my other responsibilities.

Don: Is that guilt over too much Bible reading?

David: I worry that I might have precipitated such thoughts in Anonymous, which is the last thing I wanted to do. I talk about not understanding worship and churches and religions but I absolutely do not discount the beneficial spiritual effect that these things have, including perhaps relics too, as Reinhardt and Donald were saying.

I’m just looking at all of this from from a philosophical perspective, and I will say to Anonymous that had she been born in a completely different country and never come across the Bible or any other religion I think she would still have had a relationship with the divine. It would just have been outwardly different. But there is absolutely nothing wrong with the relationship that she has.

I’m not trying in any way to cast aspersions on religion as a means of spiritual growth, and indeed that is why I’m here in this class: It is because I too am learning, and we happen to be using the Bible as the basis for our study and discussion of things of the spirit. I find it fascinating and helpful.

The last thing I want to do is sow seeds of doubt in anybody’s mind.

Anonymous: Before I started reading the Bible. I believed in relics and ritual worship and going to church once a week, but it was just outward worship. I never experienced a deep spiritual connection with God until I came to know his Word. So now I don’t believe in any other way. I even argued last week to somebody that in the end times, when freedom of worship is going to be restricted, it probably won’t affect me because if I’m worshiping God in spirit and in truth, I can worship him anywhere. I don’t have to go to church. I can worship him while I’m working, while I’m walking, whenever.

True worship has no limit. We’ve learned that from the Bible. It is not the only but it’s the most important source of knowledge about God. Over the years, you start understanding the words of God—the Bible—to be true in your life, because you’ve experienced them. They’re not just words anymore. Thank God for the Holy Spirit and for his grace, that he’s leading me into understanding more and more, through different agents, not just the Bible.

We’re growing in this class. I don’t think we’ll ever get to the end or to the bottom of it, as long as we’re constrained within our mortal bodies. I don’t think we’ll ever get to understand everything.

Reinhard: Jesus said that when two or more people gather in his name, the Spirit of God is present. So to me, even this class is part of worship, because we believe in the name of God and we have become more active participants in worshiping God by exchanging our ideas. I too don’t discount worship in church but this class, to me, adds to it. I feel we are growing, progressing, spiritually. It is very positive to me.

Anonymous: I believe God leads people to faith even if they never know about the Bible. It doesn’t have to be in a certain way. Just yesterday someone said to me: “Well, God has already decided who he wants to save.” He cited Pharaoh as an example: The Bible says God hardened his heart, meaning he didn’t want him to be saved.

I think God leads everyone. It just takes a humble heart, a desire to know, not resisting. Just go with the flow and God will lead you to salvation, to eternal life, and to understanding.

I often think of people who don’t have the advantage or the opportunity that we have to know there is a Bible and to learn about God. What about people who never heard of God? That’s something to think about.

Donald: Today, there are nine in class, sometimes there’s another four or five people. People come and go. The very nature of the way in which we come together on Saturday mornings, at a particular time, lessens our ability to provide structure to what we do. But if we were together in person, we might start adding structure to the class. There’s only a couple of rules, in my estimation, to this class. One is: We don’t need anybody who has all the answers, because we enjoy exploring ideas.

So we’re pretty good with this group, but it wouldn’t take too many traditional faith-based people to join our group and try to introduce structure to it, such as putting some topics off-limits for discussion. We have a structure of sorts, but it’s very loose, and I’m grateful for that. It is human to formalize and organize things and set parameters and button things up so that we feel comfortable.

Don: But can we do that and still allow for grace? Because grace is about what God does, whereas in our worship we tend to make it about what we do.

Donald: Thirty or 40 years ago, we were pretty comfortable in the organization that our parents showed us. And we followed it in the traditional way. Now, it might be argued that we’ve lost our way or, conversely, that we’ve gained our way! In the end, it’s about what we care about.

Don: I can remember very explicitly when I first heard the concept of grace. It is something I learned, something I grew into, something that became more and more real as I thought about it and studied it. It was basically the result of my education at Andrews and Loma Linda. When I was in medical school, we had religion classes that probably shaped my thinking more than any other individual experience that I personally had.

So I was raised in the same traditional way that Donald was raised. There were questions and there were answers, but it had nothing to do with grace and everything to do with what I was doing (or not doing).

Anonymous: So when people get to this knowledge late in their lives, is that fair, after 50 or 60 years of trying hard to please God (or even throwing in the towel)? It’s not fair that they would come to know about grace too late in life. I’m talking about myself, of course!) Maybe those who come to understand grace earlier could help others to understand it sooner, too. Life is so hard without grace.

Reinhard: For me, this class is a blessing. I travel a lot so physical participation would be difficult, but the technology makes it easy. Like the children of Israel, who were taught to talk about God’s commandments and love when they were lying down to rest, when they were eating at the table, and when they were out walking, we talk about grace all the time, and it helps our spiritual growth.

Don: Next week, we will move on from the woes of the Pharisees in Matthew 23 and look at the passage where Jesus talks about gathering like chicks under the mother hen. We’re going to talk about the wings of God.

* * *

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.