Last week, we explored the connection between grace and the Ten Commandments. We learned that grace doesn’t nullify the law but transforms it into a framework for living out God’s love in practical and sacrificial ways. The Parable of the Good Samaritan taught us that grace enables us to embody the spirit of the commandments, not as rigid rules but as an outpouring of the love we have received.

This week, we turn to an equally important question: What should we do with the grace we’ve been given? Are we meant to simply sit back and enjoy its blessings, or is there a response expected of us? And if so, what does that response look like?

Jesus addresses this in the Parable of the Talents, a story that illustrates grace as both a gift and a responsibility. He begins:

“For it is just like a man about to go on a journey, who called his own slaves and entrusted his possessions to them. To one he gave five talents, to another, two, and to another, one, each according to his own ability; and he went on his journey. Immediately the one who had received the five talents went and traded with them, and gained five more talents. In the same manner the one who had received the two talents gained two more. But he who received the one talent went away, and dug a hole in the ground and hid his master’s money.

“Now after a long time the master of those slaves came and settled accounts with them. The one who had received the five talents came up and brought five more talents, saying, ‘Master, you entrusted five talents to me. See, I have gained five more talents.’ His master said to him, ‘Well done, good and faithful slave. You were faithful with a few things, I will put you in charge of many things; enter into the joy of your master.’

“Also the one who had received the two talents came up and said, ‘Master, you entrusted two talents to me. See, I have gained two more talents.’ His master said to him, ‘Well done, good and faithful slave. You were faithful with a few things, I will put you in charge of many things; enter into the joy of your master.’

“And the one also who had received the one talent came up and said, ‘Master, I knew you to be a hard man, reaping where you did not sow and gathering where you scattered no seed. And I was afraid, and went away and hid your talent in the ground. See, you have what is yours.’

“But his master answered and said to him, ‘You wicked, lazy slave, you knew that I reap where I did not sow and gather where I scattered no seed. Then you ought to have put my money in the bank, and on my arrival I would have received my money back with interest. Therefore take away the talent from him, and give it to the one who has the ten talents.’

“For to everyone who has, more shall be given, and he will have an abundance; but from the one who does not have, even what he does have shall be taken away. Throw out the worthless slave into the outer darkness; in that place there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth. (Matthew 25:14-30)

What are the key takeaways from this parable?

Generosity: The first thing we notice is the extraordinary generosity of the master. He entrusted his servants with an incredible amount of His wealth, not as a loan or with strict conditions, but as a gift to steward. This reflects God’s abundant grace toward us. Just as the master gave freely, God gives His grace, talents, and opportunities to us without preconditions. We do nothing to earn what we are entrusted with; it is all a reflection of His goodness and trust.

According to Our Need: Next, we see that the master did not give the same amount to each servant. To one, he gave five talents; to another, two; and to another, one. This distribution was not random but intentional, based on their abilities. This teaches us an important truth about God’s Grace: He gives us what we need. To some, He gives more, to others, less. What matters is not the amount but how we respond to what we’ve been given. Grace is not about comparison but about faithfulness to the opportunities God places before us.

Do Not Hoard Grace: The most important lesson of this parable is that Grace, like the talents, is not meant to be hoarded or hidden away. It is not a static gift, something to be admired and stored for safekeeping. Instead, grace is dynamic, alive, and given to be used. The parable of the talents shows us what happens when gifts are put into action versus when they are buried. The servants who faithfully invested their talents saw them multiplied; they were commended by their master with the words, “Well done, good and faithful servant” (Matthew 25:21). But the servant who buried his talent, hiding it out of fear, faced a harsh rebuke and loss.

This lesson is equally true for grace. When grace is extended to us, it comes with the expectation that it will not remain idle. Grace is transformative by nature; it changes us, challenges us, and compels us to act. When we allow grace to shape our hearts, it flows outward into how we live, how we love, and how we serve others. Grace is most powerful when it is shared when it is extended to others in forgiveness, kindness, and service.

The danger of hoarding grace is that it becomes stagnant. Like the servant who buried his talent, we might hold onto grace without letting it transform us or others. We may fear using it wrongly or worry that it might run out, but grace is not a limited resource. God’s grace is abundant and grows as it is given away. When we share grace, it multiplies, not just in others’ lives but in our own as well. It deepens our faith, strengthens our character, and draws us closer to God.

Paul writes, “By the grace of God I am what I am, and His grace to me was not without effect” (1 Corinthians 15:10). Paul shows us that grace must have an effect, it must lead to action, to faithfulness, to transformation. Grace, when used, mirrors the heart of God. Just as God’s grace is endless and life-giving, so too is grace when it flows through us. It forgives, heals, and restores. It changes lives, both ours and those we touch. Grace, like the talents, grows in its giving, and its impact is eternal.

Freedom to Steward Wisely

Finally, notice that the master gave the talents without detailed instructions. He didn’t micromanage or hover over the servants, dictating their every move. Instead, he trusted them, giving them the freedom to decide how to use his wealth wisely and responsibly. This reflects how God entrusts us with His grace. He doesn’t force us into rigid, predefined actions; instead, He grants us free will and creativity in how we steward the grace we’ve been given.

This freedom is a remarkable gift in itself. It shows that God values our individuality and trusts us to partner with Him in meaningful ways. Just as the servants were given room to make their own decisions, we are invited to prayerfully discern how to let grace shape our lives, influence our choices, and guide our service to others. God’s grace is not about robotic obedience; it is about faithful stewardship, where we are free to reflect His love in ways unique to our callings and circumstances.

This parable also challenges the tendency of organized religion to prioritize uniformity. Too often, churches focus on standardizing practices, expecting everyone to believe the same way, serve in the same way, follow the same methods, or meet identical expectations. Evangelism programs, worship styles, and outreach strategies can sometimes feel rigid, leaving little room for personal expression or diverse callings. Yet the master in the parable didn’t impose a one-size-fits-all approach. He gave each servant talents according to their ability and trusted them to use their unique skills and creativity to steward his wealth. This reflects the beauty of God’s kingdom, where diversity is not just accepted but celebrated. God equips each of us differently and calls us to serve in ways that align with the gifts and grace we’ve been given. The parable reminds us that faithfulness to God does not mean uniformity; it means stewarding His grace in ways that reflect our individuality and the unique purposes He has for our lives.

Faithfulness Over Busyness: This parable also reminds us that God values faithfulness over busyness. Many of us have grown up with the belief that we must always be doing something for God to earn His approval, but the teaching of Jesus suggests otherwise. The master in the parable stepped back and gave the servants the space to act thoughtfully and intentionally. By doing so the Master valued quality over quantity. Likewise, God desires faithfulness, discernment, and intentional action far more than relentless activity.

Our calling is not to exhaust ourselves with endless work but to steward wisely what we’ve been given. Faithfulness means investing our time, energy, and resources where they will bear the most fruit for God’s kingdom. This requires prayer, reflection, and sometimes even resting in God’s presence to discern how and where we are called to serve. God’s trust in us, like the master’s trust in his servants, allows for freedom and focus, reminding us that it is not the busyness of our hands but the faithfulness of our hearts that truly pleases Him.

Stewardship, Not Ownership: The master’s generosity in this parable reveals a deeper truth: everything we have ultimately belongs to God. The talents entrusted to the servants were not theirs to own; they were given for stewardship, to be managed and used on behalf of the master. Similarly, all that we are and all that we have, our abilities, resources, opportunities, and even our time, are not ours to hoard or control. They are gifts from God, entrusted to us for His purposes and His glory.

This understanding shifts our perspective in profound ways. When we see what we have as God’s gifts, we move from a mindset of entitlement to one of gratitude. Instead of focusing on what we can gain or keep for ourselves, we begin to see how we can use these blessings to serve others and advance God’s kingdom. Stewardship invites us to live not for self-centered ambition but for God-centered service. It is a call to recognize that everything we hold is temporary and ultimately belongs to Him, compelling us to invest what we’ve been given wisely and faithfully for His glory and the good of those around us.

In conclusion, the parable of the talents shows us that grace is both a gift and a responsibility. It calls us to act, challenges us to be faithful, and entrusts us with the freedom to steward it wisely. But how does this relate to the relationship between grace and works? Next week, we will explore the Parable of the Sheep and the Goats, looking into how our response to grace is reflected in our actions and what this teaches us about the balance between faith and works.

For discussion, I have these questions.

- How does the idea of grace being dynamic and alive challenge the way you currently think about it?

- What might God be calling you to do with the grace you have received right now, in this season of your life?

- How does this parable prepare us for understanding the relationship between grace and works in the Parable of the Sheep and the Goats?

David: This is, to me, maybe the most difficult parable to understand. I think it requires so much in the way of assumption. We assume so much background that is just not stated in the parable itself, and that makes it difficult for me. For one thing, the assumption is made that each servant gets what they need. It doesn’t say that in the parable; it’s pure assumption. For another thing, if the parable is about grace, as we assume, then this parable makes grace conditional upon the possessor’s doing something with it. It’s not, then, an unconditional gift, and that throws a wrench into the works of our discussions on grace.

Next: whether the master, in this parable, is “generous,” as we assume, I don’t think is relevant. I mean, we know that God (the master) has unlimited resources, so it doesn’t matter how much he actually gave to each of the servants.

It bothers me too that the servants are supposed to “risk” their talents. Investment is an inherently risky business. They might just as easily have lost the talents completely, but we are apparently to assume that the market just happened to smile upon them that day. Some pro-business guy was elected president so the market shot up and their talents were doubled. If talents are grace, then that God would rely on what is essentially a form of gambling to spread his grace just doesn’t ring right with me.

So I still think we’re missing something from this parable. I wonder if, to people at the time, there would have been a context around it that would have made it make more sense to them than it does to us, but that would still require us to make some assumptions?

But one aspect of the parable that Kiran did not dwell upon is the question of the master being hard and reaping where he did not sow and gathering where he scattered no seed. It might be the critical point of the parable, for all I know. Until we’ve figured it out, I’m not sure I’m ready to accept the prevalent explanation of this parable, because it just doesn’t make enough sense to me yet.

Anonymous: This is the first time I thought of this parable this way. You’re right. It’s not a parable about grace. Otherwise, grace is not free, and we have to do something. We have to invest, and that’s amazing. The end of the parable, with the master saying, “I was a hard one, and I reap where I don’t sow” made me think that this parable probably is based upon the difference between the response of the last servant, who had the one talent, and the response of the other two.

What I mean is that the lazy servant had a wrong impression about God. Very clearly, he did not have good thoughts about God. He was fearful of God. He was seeing God not in a good light. Whereas the other ones loved their master. They wanted to do something for him. They would be happy when he came back. So maybe the point here is how we feel about God. Grace and blessings are given to everyone, but how we respond is not by investing, but by love. Because if we don’t love God and we don’t have a good relationship with Him, and if we don’t see Him in a good light—as a friend, as a source of all blessings—then, no matter what, a person who thinks like that will never want to invest. It has to come from love, from the heart.

David: So if they had gone and given the talents to some poor beggar, wouldn’t that have been a better way to invest them, rather than giving them to an investment banker? I don’t know, but I think we’re missing something.

Donald: I think it’s the investment of talent as opposed to investment of monies. I realize they’re both assets, but there’s no question that some parts of this parable make us think in terms of, “Here’s some money. Now go invest it.” The first two took a chance and they won, and the last one was apprehensive about taking a chance. I agree about their attitude toward their master. However, in some ways, he didn’t take a chance. He wasn’t willing to take a chance, maybe because of fear of the master.

But on the other hand, he might have thought, “I only have one. I can’t afford to lose one,” as opposed to, “I have five, so okay, I’ll roll the dice and see what happens.” Rolling the dice, in a parable, is just… I’m not sure about that. I think we’re mixing this. These are talents. This is not money. It is an asset, no question about it.

Why didn’t the master give everybody five? Then one person could get a better return and make ten, another could get seven and a half, and another could lose everything. Why was there a difference in the amount of talent provided to each servant? I’m not sure what that’s about. Why does one person get five, another less than that, and another even less? All of a sudden, we’re setting up a system where we’re comparing the rich guy to the poor guy. I think the poor guy is less likely to invest, just because they can’t afford to lose the one.

I’m probably taking this too literally as opposed to focusing on the point of the parable. I think we’re missing something.

Kiran: The Bible does say that it was given to each servant according to their ability. I said “according to our need” because, when it comes to grace, each of us is given what we need.

Donald: If it’s about ability, that complicates it even more, it seems to me. The one who got five has great ability, and then they double it. And the one that doesn’t have as much capacity still doubled it.

Kiran: Everyone that used it doubled it. It didn’t go up 60% or 30%; it doubled. But if you look at other parables, like the parable of the sower, even though the seeds were planted in good ground, some yielded 60, some 80, and some 100%. I guess it’s not about the outcome. It’s about what we do with the grace that was given to us.

David: I remember being so enlightened and impressed when Don led a series of talks about the parable of the sower (Matthew 13 and Luke 8). It took me a long while to understand that parable. But when I did, it was wonderful. I feel it’s going to be the same with this parable. I don’t get it yet. There’s something missing.

Anonymous: The similarities between these two parables… The sower, even though he knows this is rocky ground and it won’t produce any harvest, still sowed on it. In this parable, the master knows the lazy servant won’t do much, but he still gives him his grace. He still covers him and gives him something small to start with.

But their attitude—the rock and the lazy servant—toward God is, “No, we don’t want to work with you. We don’t like your ways. We’re not going to produce anything.” So it’s about our response to God. It’s not what God does. God is merciful and gracious. He gives to everyone. That’s one point.

The other point is, if the master knows the outcome of this lazy servant will be zero, why give him more? Why give him two or five like the other servants? He gave him something, as if not to be blamed for not giving to the unworthy. God always works with us, even though we don’t like Him, in the hope that we might come back, that we might see God’s graciousness toward us.

Reinhard: I think the parable is about responsibility. The master, which is God, of course, knows everybody—our behavior, our potential, and what we can do. In His wisdom, He understands everyone. But here, I think the focus is on how we respond to the task given to us. The same thing applies in our lives—our responsibility to respond to the talents, to what God gave us. The key is responsibility.

In life, we have something to do. Even for our salvation, we cannot just sit down and relax. There has to be something. God, in His wisdom, knows everybody—He knows the servant with five talents, two talents, and one talent. He already knew the outcomes. God can see the outcome. This is the responsibility for us to give back or to do what God wants us to do. We cannot sit idle; there has to be something. It’s the same thing with salvation. Although the Bible says salvation is not by our works, but by the grace of God, there still has to be a response.

Grace is forgiving, but it’s not entirely unconditional. It’s not just free. We have to do something—that’s our task as believers. The grace of God is free to everyone, but we have to respond by doing something about the challenge ahead of us. God knows what we need to do, but we have to act on our own.

Sharon: I was agreeing with David on the confusion aspect of the point of this parable. So I posed the question to Co-pilot AI about the relationship between grace and this parable, and it replied:

“In the parable, a master entrusts his servants with different amounts of money before going on a journey. Upon his return, he rewards the servants who have used their talents wisely and productively, while the servant who hid his talent out of fear was reprimanded. Here’s how the parable relates to grace:

- Grace and Entrustment: The master gives the talents to his servants based on their abilities, showing trust and grace. This act of entrustment is not earned by the servants but given freely, much like how grace is given to us by God without us earning it.

- Grace and Opportunity: Each servant is given an opportunity to use their talents. This mirrors the opportunities we receive through God’s grace to use our gifts and abilities for His purposes.

- Grace and Accountability: The master holds the servants accountable for how they use their talents. This accountability is a form of grace, encouraging growth and responsibility. It shows that grace is not just about receiving but also about how we respond to what we’ve been given.

- Grace and Reward: The rewards given to the faithful servants are also a form of grace. They are invited to share the master’s happiness, symbolizing the joy and fulfillment that comes from living in accordance with God’s will.”

In essence, the parable teaches that grace involves both receiving and responding. We are given gifts and opportunities by God’s grace, and we’re called to use them faithfully and wisely.

I rest, and I give credit to Co-pilot.

David: Are we to conclude, then, that the two gamblers were wise while the poor hoarder was just dumb? Isn’t he the kind of guy upon whom Jesus would lavish grace? Yet here, Jesus is talking about throwing this poor schmuck into outer darkness because he’s not a smart investor and doesn’t know how to gamble! That just doesn’t add up. We’re missing something.

Don: I think that the one with one talent is put into outer darkness not because he didn’t invest his talent, but because he thought he could speak for God. His failure to do what the Master wanted had to do with his view of God. There may be something in that we’re missing—the notion that we can somehow interpret God’s ways, that we can know His ways, and that we can base our actions on our knowledge of God’s ways. This, to me, is what’s fatal. It’s a form of religion that puts us into outer darkness.

So I don’t think it’s about the outcome of the investment as much as it is the idea that I can interpret God, that I can know God, and that I can make my own responses based on my knowledge of God. That, to me, is fatal religion.

Carolyn: I keep thinking about Jonah and how God worked to impress upon him the importance of obedience, even to the point of being swallowed by the great fish, which changed his mind. But here, I see no redemption in this man with the one talent. As a child and growing up, I always felt sorry for him. If I had five talents and lost one, I’d still have four to invest. But if I only had one, I’d be scared to try and lose it. If I lost it, what would happen? I wouldn’t have anything left for the master. So, I understand his fear of wanting to please the master. Jonah was outright defiant, but God worked hard to turn him around. With the man with the one talent, I see no redemption, and I’m struggling to put a handle on that.

David: A critical point! Carolyn feels sorry for this guy. I bet there’s not one of us here who doesn’t feel sorry for him, who thinks he got what he deserved. We all feel sorry for the guy, and I can’t believe that Jesus didn’t!

Donald: I don’t know that if you feel sorry for him, you’d call him lazy. To me, it’s somewhat like the guy on the corner asking for money. He gets a little bit—do you think he’s going to go start investing it? He’s desperate. With the one talent, or one piece of whatever it is, he’s desperate.

So there’s something missing, it seems to me, that’s challenging for us to understand. It might have to do with the relationship this servant had with his understanding of God. This parable, I think, is really trying to teach us more about God than about the people receiving the talents.

Anonymous: I think what Dr. Weaver and Carolyn said is adding to my understanding. Jonah, all he had to do was be obedient—just do what God told him to do. This servant, too—all he had to do was be obedient to God, just do it. If these two individuals had the right view of God, they would have obeyed without analyzing His character—or, in Jonah’s case, without letting his feelings toward Nineveh get in the way.

Let’s not analyze God, as Dr. Weaver said. We can’t speak for God. Whatever He wants, we should obey. That’s the first step toward grace—productive grace, life-changing grace, redemptive grace. These two individuals, Jonah and the man with the one talent, would have had their lives changed if they had simply taken the master’s order and done it. If they had been obedient.

David: But as I read this, all three were obedient. The master didn’t tell them to go and make more money. He just told them to keep it. In a sense, none of them was disobedient. The NIV Bible even calls the talents “bags of gold.” So he gave one servant five bags of gold, another two bags, and another one bag, each according to their ability. Then he left. That’s all it says. He entrusted his wealth to them.

That’s the word: “entrusted.” I guess you can read into that what you like. Did he entrust them to make more money with it or to simply keep it safe? The guy with the one bag of gold obeyed the instruction, it seems to me. In fact, he might have been wiser because he didn’t take any risks with it. The two who risked it in investing could have lost it all—they were arguably irresponsible with the trust placed in them.

So I repeat: we’re missing something in this parable. I’m sure it’s very important, and I’m sure there’s a message here that Jesus is trying to convey. But I think we need to keep digging.

Donald: What I’m reading here is that God expects people to use the gifts and abilities He has given them wisely and diligently. So the operative term there is “use.” Obviously, however, there’s a big difference between “use” and “hedge your bets”—you know, gambling with the money.

Kiran: Suppose someone uses their investment—not everybody is supposed to get double. The best you can get might be 10%, or maybe 8%. Some might get 12%. There should be some sort of diversity in the outcome. But in this parable, by saying that both of them got double—100% return—it suggests that the risk of investing isn’t there.

David: Then suppose the parable had said that God gave them grace, not “talents,” and then they went out and invested that grace. To me, there would be no risk involved. Whether it doubled or was wasted does not matter—what matters is that the attempt was made. There is no risk in sharing grace in the same sense as there is risk in investing money—gold, talents. The parable doesn’t seem to be about grace. If it were about grace—if Jesus had said “grace” instead of “talents”—I’d have no problem with this parable.

Donald: And it would make perfect sense with the person who was given the one talent. Because if they didn’t even share grace at all and just buried it, then they’d be held accountable. So the question is: what asset are we actually talking about? Are we talking about talents? About gold? Or are we talking about grace?

Reinhard: I like the idea that there’s no risk when God gives these talents to you. But in reality, when we don’t do our job, there is a risk. If we don’t apply ourselves or meet the requirements, there are consequences. I think it’s the same in life. Maybe we don’t produce 100%, but we have to produce something.

In life, we have to share. If we consider this talent as grace given to all of us, then the risk ties back to the responsibility. We have to do something with the grace given to us.

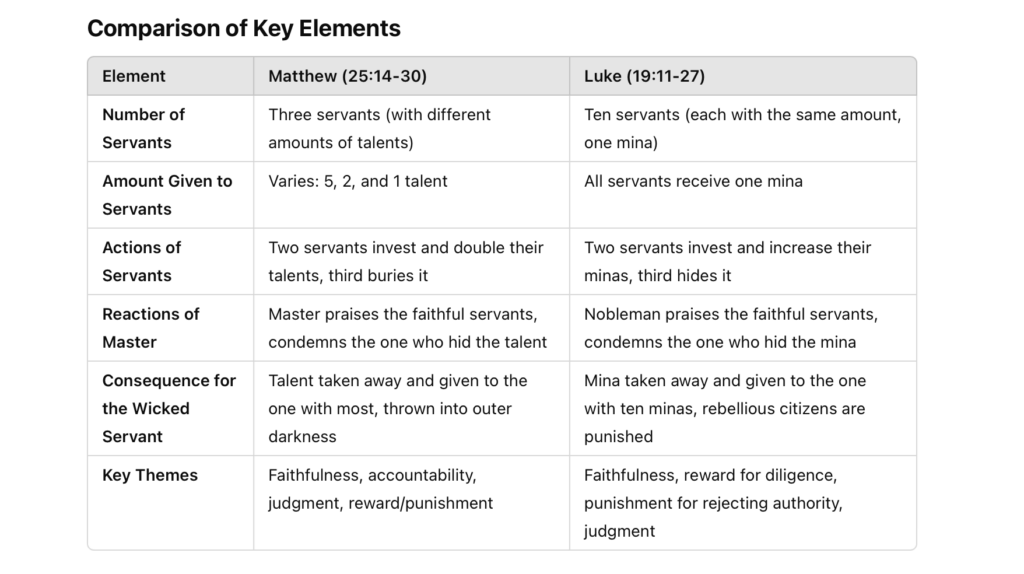

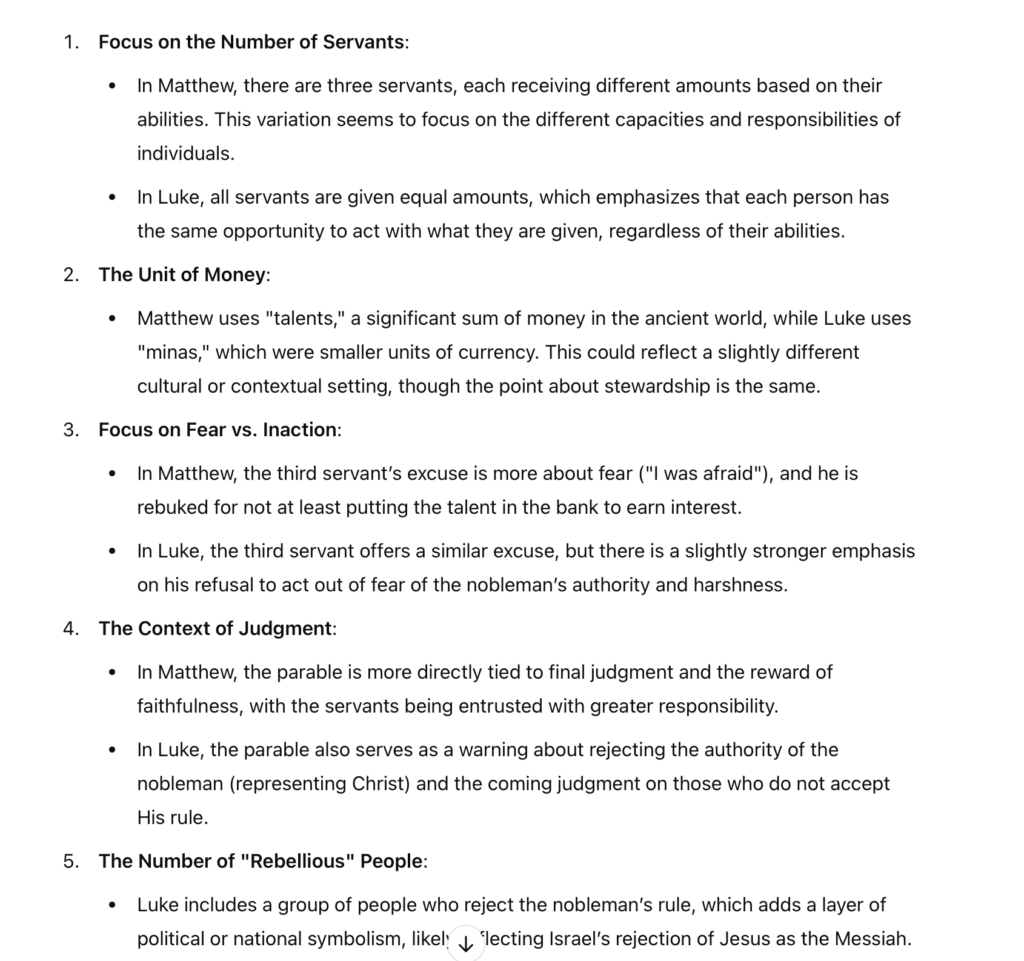

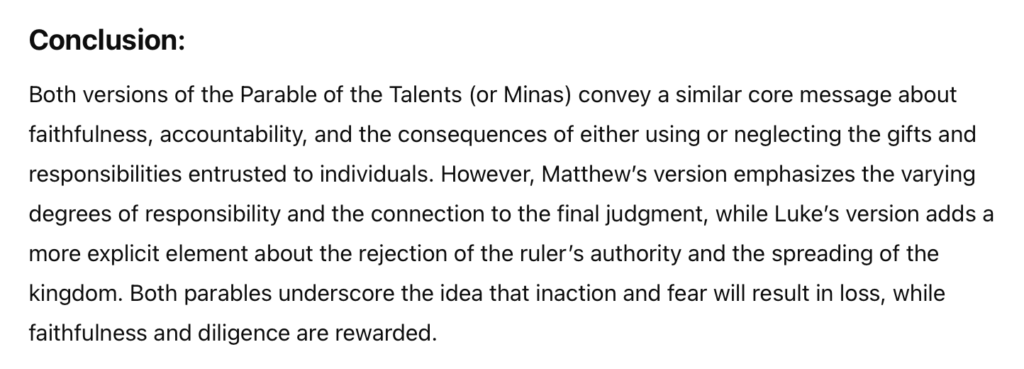

Anonymous: Luke’s version of the parable (Luke 19:11-27) has some differences.

The Parable of the Ten Minas

While they were listening to this, he went on to tell them a parable, because he was near Jerusalem and the people thought that the kingdom of God was going to appear at once. He said: “A man of noble birth went to a distant country to have himself appointed king and then to return. So he called ten of his servants and gave them ten minas. ‘Put this money to work,’ he said, ‘until I come back.’

“But his subjects hated him and sent a delegation after him to say, ‘We don’t want this man to be our king.’

“He was made king, however, and returned home. Then he sent for the servants to whom he had given the money, in order to find out what they had gained with it.

“The first one came and said, ‘Sir, your mina has earned ten more.’

“‘Well done, my good servant!’ his master replied. ‘Because you have been trustworthy in a very small matter, take charge of ten cities.’

“The second came and said, ‘Sir, your mina has earned five more.’

“His master answered, ‘You take charge of five cities.’

“Then another servant came and said, ‘Sir, here is your mina; I have kept it laid away in a piece of cloth. I was afraid of you, because you are a hard man. You take out what you did not put in and reap what you did not sow.’

“His master replied, ‘I will judge you by your own words, you wicked servant! You knew, did you, that I am a hard man, taking out what I did not put in, and reaping what I did not sow? Why then didn’t you put my money on deposit, so that when I came back, I could have collected it with interest?’

“Then he said to those standing by, ‘Take his mina away from him and give it to the one who has ten minas.’

“‘Sir,’ they said, ‘he already has ten!’

“He replied, ‘I tell you that to everyone who has, more will be given, but as for the one who has nothing, even what they have will be taken away. But those enemies of mine who did not want me to be king over them—bring them here and kill them in front of me.’”

David: “Bring them here and kill them in front of me”?! He certainly was a pretty hard man, wasn’t he?

Anonymous: I want to share with you what I studied this week. It has something to do with the Sabbath, with grace, and also with this lesson. About a month ago, I heard that a certain denomination—I’m not sure which one—believes Jesus’ resurrection wasn’t on a Sunday, which means He wasn’t crucified on a Friday. I read about it and found it logical at first, but this week I revisited it because it stayed on my mind, and I wanted to understand more.

I spent two days studying this, going from one Bible verse to another, trying to make sense of what they were saying. After probably wasting four hours on this, it just dawned on me: how clever Satan is! He kept me busy and distracted from the core of the issue—the most important part of the story. Then things started to make sense to me.

When I studied the Passover as the first day of the Feast of Unleavened Bread, which lasts for seven days, I realized the significance. The Passover is the Lamb slaughtered for us, followed by the week of unleavened bread. This starts with a ceremonial Sabbath and ends with another ceremonial Sabbath. I remembered that anyone who broke the Sabbath would be cut off from their people, which means they’d be killed. This brought me back to the idea of “kill them in front of me.” It’s the same principle.

For example, those who gathered manna on the Sabbath were killed. As I meditated on this, the connection between the crucifixion of Jesus on Passover and the ceremonial Sabbath that followed became clearer. The unleavened bread represents living without sin, and the ceremonial Sabbath teaches us that we are not supposed to do anything for the plan of salvation—just as we are to rest on the Sabbath, both weekly and ceremonial. Jesus, the Passover Lamb, took sin upon Himself so we could live sinless lives.

The week of unleavened bread symbolizes the duration of our lives. It begins with rest in Jesus’ sacrifice and ends with rest in eternal life, with sinless living in between. The first and last Sabbaths of the Feast show that Jesus not only initiates our salvation but also brings it to completion.

This whole understanding helped me see the Sabbath not as an obligation or an order to be kept out of fear, but as a profound symbol of the plan of salvation and God’s grace. The slaughtering of the Lamb is the first step, and it leads to our rest in Him. The Sabbaths bookend a life of sinlessness, made possible by grace.

Kiran: That’s profound.

Don: Very well said. We have much to ponder for the week.

* * *

Appendix: Comparison of the Two Parables (courtesy of Donald)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.